By John Richardson

READERS OF THE blog over the last 12 years shouldn’t be at all surprised by this 21 May Financial Times article by Ruchir Sharma, chair of Rockefeller International.

“Something is rotten in the Chinese economy, but don’t expect Wall Street analysts to tell you about it,” he wrote.

For example, Wall Street’s assumption of 5% China GDP growth in 2023 would suggest corporate revenue growth of 8%, but it rose by 1.5% in the first quarter, Sharma added.

Imports dropped by 8% in April and credit growth last month increased by only half as much as had been forecast. Youth unemployment hit 20% and was rising, said the Rockefeller International chair.

Since 2008, China’s economic model had been driven by government stimulus and rising debt, especially in property markets, he continued.

Chinese debt servicing now accounted for a third of disposable income and excess savings in China were equal to only 3% of GDP compared to 10% in the US, said Sharma.

He added that China’s GDP growth potential was only half of its 5% target for 2023 due to a shrinking population.

“A growth model dependent on stimulus and debt was always going to be unsustainable and now it has run out of steam,” Sharma added.

The property market had fallen into a debt crisis. The increasing inability to finance the debt had reverberated across markets, resulting in industrial sectors slowing at a quicker rate than consumer-related firms, he said.

Fellow blogger Paul Hodges and I first highlighted China’s debt and demographic risks in 2011 in the ICIS/New Normal Consulting e-book, Boom, Gloom and the New Normal. The publication of the book occurred shortly after I launched the Asian Chemical Connections blog.

We weren’t, of course, able to say when China’s debt and demographic problems would come to a head. But since 2011, we’ve kept our readers regularly informed of the key milestones on the road to where we’ve arrived today – permanently much lower GDP and chemicals and polymers growth.

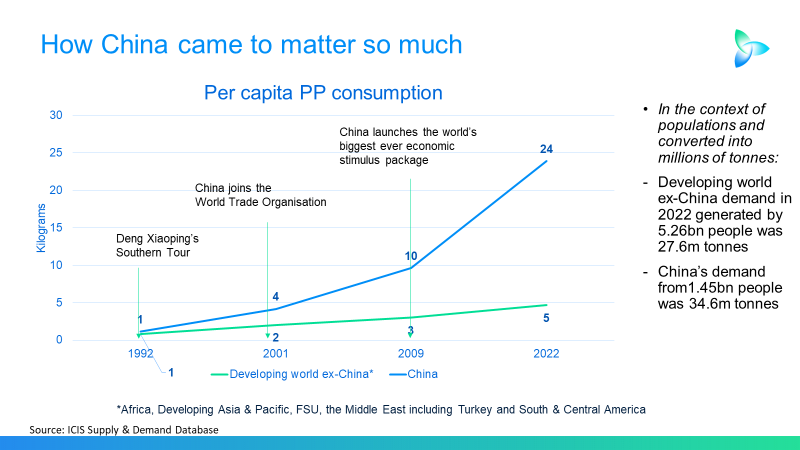

For the benefit of those who haven’t followed our work over the past 12 years, the chart below provides some historical context. It is from my presentation at last week’s Asia Petrochemical Industry Conference in New Delhi.

The history behind China’s PP demand boom

The patterns of per capita polypropylene (PP) consumption growth in China and the rest of the developing world that you can see in the chart are identical – and this is no exaggeration – in all the other chemicals and polymers.

Deng Xiaoping’s tour of China’s southern provinces in 1992 led to the gradual liberalisation of the economy. Private investment, supported by vast government spending, subsequently led to China becoming the manufacturing workforce of the world.

The revenue growth of China’s export-focused manufacturers was then turbo-charged by the country’s admission to the World Trade Organisation. This removed all the tariffs and quotas that had restricted China’s exports to the West, allowing it to take maximum advantage of a youthful population.

But in 2001, China’s births per woman first fell below the population replacement rate of 2.1 and was below this level in 2009 – the next pivotal year (see later chart). This was when China launched the world’s biggest-ever economic stimulus package.

The stimulus package – which involved an explosion in credit availability for spending on real estate, infrastructure and manufacturing capacity – masked the economic drag of worsening demographics.

The chart shows that in 1992, China and the rest of the developing world’s per capita PP consumption were each about the same at 1kg per person.

By 2001, the gap was big but not gargantuan as China was at 4Kgs with the developing world ex-China at 2kgs.

But just look at how the two trend lines then diverged: By 2009, the gap was at 10kgs versus 3kgs and by 2022, it was at 24kgs versus 5kgs.

Now let us convert the 2022 numbers into millions of tonnes and place them into the context of populations:

- Developing world ex-China PP demand was 27.6m tonnes from 5.26bn people.

- China’s demand was 34.6m tonnes out of a population of 1.45bn people.

The next chart tells us that China’s PP demand growth (again, it is the same in all the other chemicals and polymers) has way outperformed its growth in incomes. This is because of the three historic events detailed in my first chart.

The chart shows how in 1992, the developed world’s per capita PP consumption was at 12kgs versus China’s 1kg. This was perfectly sensible when one considers that China’s per capita income was just $400 compared with the developed world’s $19,019, based on current prices.

In 2001, PP consumption versus income patterns had yet to go badly out-of-kilter. Developed world PP per capita consumption was 18Kgs with its per capita income at $19,954; China was at 4kgs and $1,045/tonne respectively.

But the chemicals world had become alarmingly unbalanced by 2009. Developed world PP per capita consumption had slipped to 17kgs compared with a per capita income of $36,793. This was versus China at 10kgs and $3,813.

This was nothing, though, compared with the completely unsustainable situation we were in last year. The developed world was at 19kgs and $47,857 and China at 24ks and $12,970.

There has only ever been one flaw with the theory that China is becoming a middle-class country by Western standards: The data.

China is decades away from catching up with the West in terms of average incomes, assuming this can happen at all given its debt and demographics challenges, and yet:

- In 2022, from a population of 1.14bn, and as I said, a per capita income of $47,857, the developed world consumed 22.6m tonnes of PP.

- But from a population not that much larger – 1.45bn – and from a per capita income of just $12,970/tonne, China consumed 34.6m tonnes of PP.

The future of China’s PP demand

The chart below explains why we are where we are today.

No country the size of and economic importance of China has seen a demographic crisis on this scale before.

The trend line shows the fall in births per woman from the peak of 7.5 in 1963 to just 1.2 in 2022. As mentioned earlier, China’s births per woman first fell below the population replacement rate way back in 2001 and have stayed there every year since then.

Economic growth is being dented by the fall in family formations as fewer young couples get married. This is the result of both the greying of the population and the 112 boys born to every 100 girls in 2021, which is the latest data I could find.

“New family formations in China have been declining since 2013 alongside the falling marriage rate, the by-product of decades of China’s one-child policy,” wrote the Council on Foreign Relations in this 21 March article.

The decline in the growth of new families is, of course, affecting housing demand, as is the end of the old government “put option”.

Beijing had guaranteed that property prices would never fall, making investment in multiple properties a gamble obviously worth taking. But since 2021, real estate prices have fallen, badly denting confidence in a sector that’s worth some 30% of China’s GDP.

There must surely be pressure to save more to cover the rising pension and healthcare costs resulting from an ageing population during a period when, as Sharma wrote in the FT, excess savings in China were equal to only 3% of GDP compared to 10% in the US.

The tried and tested approach to boosting GDP was investment in infrastructure. But now:

- Local governments, which are responsible for 70% of total government spending, are struggling to raise money for new bridges and roads because local government financing depends on rising land prices. Land prices are falling.

- Most of the infrastructure that needs to be built in China’s most-populous provinces has been built. Therefore, when the remaining infrastructure that needs to be built is built in the less populated provinces, the economic multiplier effect will be more muted.

This section of the post explains the chart below.

As I warned in my January outlook for China’s polyethylene (PE) market in 2023, the market got ahead of itself because of the mistaken idea that there would be big surge in consumption once the January Lunar New Year holidays.

The theory was that the end of the zero-Covid restrictions would lead to a big bounce back in the economy.

But I said that while services spending would recover, debts, demographics and a decline in China’s exports because of high inflation would mean a muted recovery. I was right.

Misplaced optimism led to what thought was overstocking of PP because year-on-year imports increased in Q1 despite the weak fundamentals. In April over March, imports fell from 342,244 tonnes to 262,793 tonnes.

An increase in Q1 2023 imports over the same period last year suggested that this year’s demand growth might reach 3% versus 2% in 2022.

But the fall in April imports combined with cuts in some local production now suggest demand growth of minus 1%. I understand that China’s powder-based PP plants, which tend to suffer from competitiveness issues, are running at low rates.

Conclusion: Getting used to low single digit or even minus growth

Sure, it is too early to make a clear call on this year’s PP demand. The recovery from zero-Covid may gather speed over the remainder of the year, leading to growth higher than my estimate of minus 1%.

But the inevitable recovery in service activity, following large swathes of the economy being shut down during zero-Covid, could amount to a “head fake”.

I believe we have entered a permanent period of lower China chemicals demand growth, which will be in the low single digits of perhaps even negative during some years.