By John Richardson

THIS 20 AUGUST article in the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) underlines how the views that Paul Hodges and I have been expressing on China since 2011 have now become fully accepted.

We of course couldn’t say way back in 2011 when the moment would arrive when China’s demographics and debts would become economically defining problems. But we did say that chemicals companies needed scenarios, Plan Bs, for when the inevitable happened.

The turning point came in late 2021 with the financial difficulties of Evergrande, the property developer, and Beijing’s response. Its decision not to launch a full rescue package was indicative of its commitment to building a new economic growth model.

The WSJ said that China was running out of new bridges, roads and airports etc. that needed to be built, making the old “pump priming” of the economy through infrastructure spending much harder.

A sign of this saturation point was the COVID-19 centre, the size of the three football fields, that was being built in Yunnan province despite the end of the pandemic, said the WSJ.

Then there’s the real-estate bubble. About one-fifth of apartments in urban China, or at least 130m units, were estimated to be unoccupied in 2018, according to a study by China’s Southwestern University of Finance and Economics cited in the WSJ article.

Another WSJ article, published on 19 August, quoted data from China’s National Commission on birth rates per woman last year. The birth rate was said to have fallen to 1.09, which would make it even lower than Japan’s, a much richer country.

This is reflected in my updated chart below, which also lists some of the other challenges facing China’s economy – along with a worrying quote from the second WSJ article.

China may be able to build a successful new economic growth model, centred on higher value “green” manufacturing and services. This is an argument I’ve been making for several years.

But good scenario planning must factor in various degrees of success or failure in building such a model.

And even complete success would surely mean that GDP growth would be lower than the commodity intensity investment-led growth seen over the last 30 years. This would obviously mean a deceleration of chemicals demand-growth rates.

The $64,000 dollar question thus becomes what the future chemicals growth rates are going to be.

Global capacity exceeding demand to reach 26m tonnes in 2023-2030

The chart below – building on my previous post on high density PE (HDPE) – largely reflects the extent of the slowdown in China.

If you want the details by grade – HDPE, low-density PE (LDPE) and linear-low density PE (LLDPE) – contact me at john.richardson@icis.com.

Average annual capacity exceeding demand was 10m tonnes in 2000-2022 with the average annual operating rate across the three grades at 86%. But average annual capacity exceeding demand is forecast to be 26m tonnes in 2023-2030 with the operating rate at 80%.

Let us break the world down into the three mega-demand regions – the Developed World, the Developing world ex-China and China – in order to consider demand-growth percentages (actual in 2000-2022 and our base-case forecasts for 2023-2030).

As recently as three years ago, consensus views on China’s chemicals and polymers growth in general were that it would be at 6-8% per year over the long term.

But we see China’s PE demand growth falling to 3.3% in 2023-2030 versus 8.7% in 2000-2022. We also see a growth deceleration in the Developing World ex-China, but a growth pick-up in the Developed World.

What would be required, under these outcomes, to get the global operating rate back to its 2000-2022 average of 86%? See the chart below.

I’ve removed the demand and capacity numbers on the left-hand axis. If you need these numbers, again contact me at john.richardson@icis.com.

My rough estimate (roll-on AI, please, as this takes a lot of time and is of course prone to human error) is that global capacity between 2023 and 2030 would have to be a total of some 11m tonnes/year lower than our base case to get back the historic operating rate of 86%.

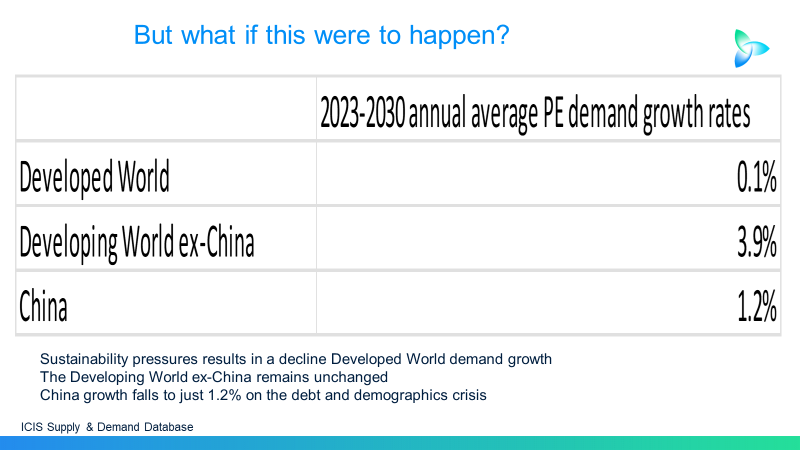

But consider table below with downside forecasts for PE growth in 2023-2030.

One can argue that sustainability pressures will result in lower, rather than higher, PE demand growth in the Developed World. There are the downward pressures on consumption from re-design and re-use – along with the restrictions and bans affecting single-use plastics.

I have guesstimated 2023-2030 Developed World demand growth at 0.1% and Developing World ex-China growth the same as our base case. I’ve lowered China’s growth to 1.2%.

The effects are modelled in the chart below with the left-hand axis again removed.

Under these outcomes, global capacity in 2023-2030 would need to be at a total of 23m tonnes/year lower than our base case to achieve the 2000-2022 average operating rate of 86%.

Demand would be 67m tonnes lower than our base – 47m tonnes down to a worse China outcome and 20m tonnes down to slower-than-expected growth in the Developed World. In other words, this would be a 69% to 31% split, underlining the over-reliance on China for growth.

The downturn’s Winners and Losers

See below my thoughts on how we should categorise the Winners and Losers in this downturn. More on the sustainability theme in my next blog post.

The Losers may include smaller chemicals and polymers companies that are not integrated upstream to at least refining– and, ideally, also oil and gas production. It is among these producers where we could see most of the shutdowns to bring PE markets back into balance.

The Winners could be the big integrated chemicals companies – at least upstream to refining, and, as I said, ideally to oil and gas production. The US and the Middle East have the chance to win more market share.

I also see a “battle for carbon” developing as the big integrated producers build new complexes that secure “green price premiums”. This will be through selling chemicals and polymers that are certified as having generated lower Scope 1 carbon emissions than their competitors.

Today’s downturn is going to accelerate the development of new business models centred on sustainability.

The Winners should surely also include the converters and the brand owners. They have huge opportunities to save money on their chemicals and polymers purchases because of today’s levels of oversupply. But they need to closely monitor the risks of their suppliers shutting down.

The successful converters and brand owners also need to increase their sustainability push. The cost of carbon should, I believe, become as big an area to focus as recycling.

The long-term opportunities from “less is more” are huge. But today’s downturn is what it is. It doesn’t help anyone to argue otherwise, in my view.