By John Richardson

MOST of the analysis on the tenth anniversary of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) focuses on the effects on Western economies and societies. Economic inequality has risen since 2008 resulting in the rise of populist politics, is a very common theme.

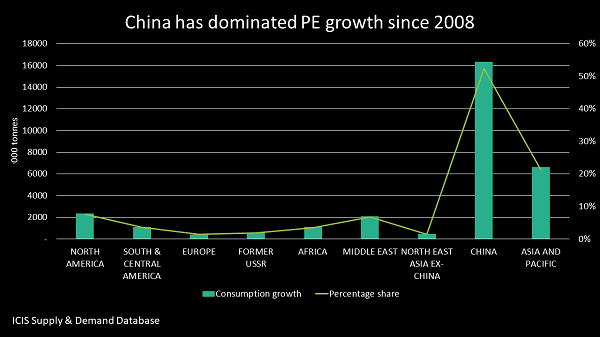

But almost entirely overlooked is the huge effect that the GFC had on China. We can see this very clearly in the extraordinary data on the growth in polyethylene (PE) consumption (the pattern is very similar in other polymers including polypropylene):

- Between 2000 and 2007, China accounted for 31% of global PE consumption growth as against 7% in North America and 15% in Europe.

- But from 2008 to 2017 China’s share of global demand growth jumped to 52% as Europe’s share fell to just 1% because of maturing markets and macroeconomic problems.

Digging further into the data and you’ll find that in 2000-2007, 76% of the growth in PE consumption was in the developing world (South & Latin America, Africa, the Former Soviet Union, the Middle East including Turkey, China and the Asia and Pacific region. This region includes India, Pakistan, the rest of south Asia and Southeast Asia).

In 2008-2017 the percentage of PE demand growth accounted for by the developing world increased to 86%.

Why did this happen post-GFC and what does this tell us about the future?

Short-term implications: A new global recession centred on China

One of the main reasons why petrochemicals and polymers demand growth in general went through the roof in China in the period immediately after the GFC was the biggest economic stimulus package in global history.

China’s leaders faced the prospect of tens of millions of lost manufacturing jobs in early 2009 as a result of cancellation of export orders from the West. This would have been a major threat to social stability.

So bank lending was tripled in 2009 versus the previous year as banks were told to go out and lend, regardless of the viability of loans.

The priority was the economic multiplier effect of building condos, chemicals and other manufacturing plants for the sake of building plants. Little regard was given to the long- term effects on supply and demand.

This economic largesse boosted growth across the rest of Asia and the rest of the developing world. And because China could not build steam crackers quick enough to deal with the resulting surge in PE demand, its imports increased. This was of great benefit to PE exporters struggling with weak demand at home because of the GFC.

In the eight years from 2000 until 2007, China’s PE imports (imports minus exports) rose by 1.5m tonnes. But in the eight years from 2008 until 2015 they increased by 5.2m tonnes.

Ever since 2008, China’s economic stimulus has seen several episodes of surge and decline. The latest decline began in January of this year.

Lending via the highly speculative shadow banking sector was down by $603bn in January-August 2018 versus the same period last year, according to the People’s Bank of China. Total Social Financing, which is lending via both the shadow banks and the state-owned banks, was $244bn lower.

This latest reduction in credit is another attempt by China to deal with bad debts built up because of the huge post-GFC stimulus package. Economic activity is also slowing down because of factory closures resulting from the world’s biggest-ever environmental clean-up.

These reforms are occurring as the US and China are embroiled in an economic growth-sapping trade war.

Yet most reflections on ten years after Lehman Bros barely touch on these themes, as the link isn’t made between China’s debt problems and the GFC.

Neither do most commentators recognise the scale of today’s credit dial-back by China. Financing via the shadow banking system, which fuelled China’s property bubble, is now back at levels before the GFC.

What is also still not widely understood is the global scale of China’s economic stimulus. Since 2009, half of the $33 trillion of central bank stimulus pumped into the global economy has come from China.

There is clearly a risk that the trade war combined with these Chinese economic reforms will tip the world into a new recession – especially when you also consider the rise in emerging market dollar-denominated debt since 2008.

This rise in dollar debt is result of record-low interest rates which are now being reversed. The Fed plans to raise borrowing costs on four more occasions over the next 12 months.

Further, there is the economic ripple effect across the rest of the developing world of China’s stimulus withdrawal.

China will have less money to trade with the rest of the developing world, and to spend on infrastructure investments as part of its Belt and Road Initiative, particularly if the stimulus withdrawal continues to coincide with the trade war.

The trade war will, in my opinion, continue throughout 2019 and beyond because it is a geopolitical as well as economic in nature.

This threatens a new global recession. And it obviously also threatens PE and other petrochemicals and polymers growth in what has become very much a China-centred petrochemicals world.

Long-term implications: US PE producers in big trouble

Between 2018 and 2025, 87% of global PE consumption growth will be accounted for by the developing world – in other words no major change from the 2008-2017 period.

China will also remain the main driver of global net imports. In 2008-2017 it accounted for 52% of net imports and in 2018-2025 this percentage will remain unchanged.

And between 2018 and 2025, its PE imports will grow by a further 3.6m tonnes. In second place will be Asia & Pacific. Its imports will grow by 2.7m tonnes.

This tells us these that the great prize will remain firstly the China PE market followed by PE markets in the other developing countries, regardless of short term declines in growth for the reasons outlined above.

It also tells us that the developed markets of the North America, Europe and Northeast Asia ex-China (South Korea, Taiwan and Japan) will continue to see very little growth.

China’s extraordinary increase in PE demand is not just down to the GFC. The economy has become much more domestic as opposed to export-driven as a result of rising per capita incomes.

The huge boom in mobile internet sales is another non GFC-related factor behind strong PE demand growth.

And because China remains the great prize for the PE industry, good relationships with China are essential for exporters.

US PE producers are as a result in a very vulnerable position.