Note that all the data comparisons below are on a year-on-year basis

By John Richardson

THE PROVERBIAL light bulb came on early last month, thanks to this article from Trade Data Monitor (TDM) which analysed China’s strong July exports and made the point that they were driven by a big change in lifestyles.

Many of the things we need to spend more time at home are supplied by China, hence the big jump in its July exports of electronics whilst its shipments of bags for travel collapsed. This has huge broader implications for the global economy, and for petrochemicals, which I’ve discussed in several posts, including this one.

The light bulb has shone brighter, thanks to another article from TDM which analyses China’s August exports that were up by 9.5%. Now, perhaps, we have some of the explanation for the polyester mystery I discussed on Monday.

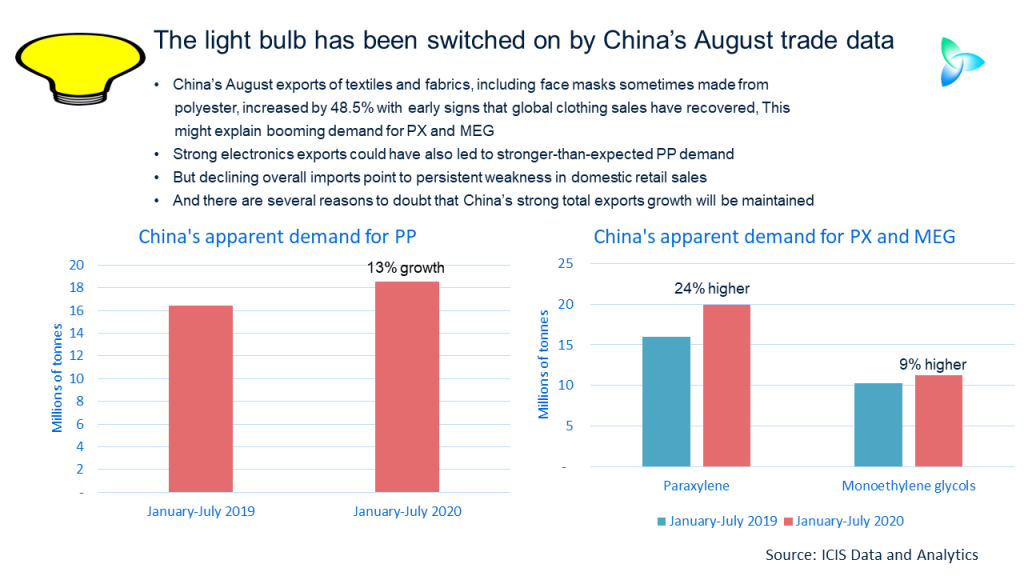

China’s January-July apparent demand for paraxylene (PX) was up by 24% with mono-ethylene glycol (MEG) consumption 9% higher, despite the global collapse in garments demand and a 23% fall in China’s net exports of polyester fibres, films and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) resins.

“Exports of textiles and fabrics including the protective medical masks everybody is wearing increased 48.5% to $14.7bn,” wrote TDM in their latest article (face masks are partly made from polyester and cotton blends).

But this cannot be the only reason why China’s apparent demand for PX and MEG was strong in January-July given that, of course, it takes a great number of face masks to on a volume basis replace the lost sale of just one T-shirt.

What also seems likely is that the recovery in clothing sales in the West, which has occurred since lockdowns have eased, has been anticipated by China’s PX and MEG buyers and producers. PX and MEG stocks could have been built up in January-July in anticipation of better demand for polyester fibres during the remaining months of this year. I say anticipated because up until July the data show weak overseas Chinese garment sales.

But the surge in Chinese exports of face masks does seems to tell us one thing: The nature or composition of petrochemicals end-use demand has been radically reshaped by the pandemic, requiring a much more complex bottom-up methodology for estimating consumption growth. Using multiples over GDP has become an almost entirely redundant approach.

More prosaically and more immediately, it could mean there is no overstocking in Chinese PX and MEG if you combine strong demand for textiles and fabrics exports, including the polyester and cotton blends sometimes used to make face masks, and a nascent recovery in global garment sales in the West. But there is the risk that garment sales will decline again if the number of coronavirus cases surges again during the northern hemisphere winter.

“In August, exports of mobile phones increased 23.3% to $9.9bn. Shipments of high-tech products rose 12% to $67.1bn,” added the same TDM article.

This might explain why, as I discussed last Friday, China’s January-July apparent demand growth for polypropylene was up by 13%, implying 1.1m tonnes of overstocking based on our estimate for full-year 2020 real demand growth. And it could be the reason why, based on local styrene (SM) derivatives consumption, January-July overstocking in SM appeared to be around 500,000 tonnes. PP and SM derivatives such as acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) are used to make electronics.

But while, very sadly, demand for exports of textiles and fabrics that go into face masks looks likely to be sustained for several years, we cannot say the same for high-tech electronics. There are only so many iPhones that the developed world needs to buy. What happens when most of us have finished kitting out our homes as offices – for example, when we’ve bought the laptops we need, made from PP and ABS?

How will the Western world’s ability to buy consumer goods in general be affected by the withdrawal and restructuring of government stimulus schemes? These schemes have been particularly important in bolstering the incomes of lower-paid workers.

Sadly again, I fear I know the answer to all these questions. We have only seen the first wave of economic damage from the pandemic and the waves will keep coming as we are several years away from an effective vaccine. Dysfunctional politics and lack of resources to test, trace and isolate in developing countries mean the only solution, in my view, is a universally administered and effective-enough vaccine. The residual economic damage to the developing world could last a generation.

The domestic growth problem

China might see several more months of strong export growth. It could, for instance, take several more months before cutbacks in government stimulus in the West affect spending on consumer electronics etc. Renewed outbreaks of the virus during the northern hemisphere winter might likewise take a while to work through into some of China’s export data. It might also be several more months before most of us have finished converting our homes into offices.

But what we have already seen is a clear failure to match strong export growth with an equally strong recovery in domestic consumption. Ten years ago, this wouldn’t have been as important for China’s petrochemicals demand. But the domestic economy is now a bigger driver of consumption than exports.

What represents failure is the 10% headline decline in China’s retail sales in January-July. Why I say headline is because China’s official retail sales include government spending at shops and restaurants. The real decline in retail sales will therefore be greater than 10%.

The problem China faces is that its post-pandemic economic stimulus has mainly favoured higher-income workers. Its ability to redress the balance through cash handouts to low- and average-income earners is constrained by the highest food price inflation in a decade, a result of the damage to agricultural production caused by the recent floods (cash handouts risk adding to inflation). The floods are also delaying infrastructure work, a key part of post-virus stimulus.

And while China’s imports, as I said, grew by 9.5% in August its imports fell by 2.1%, the second month in a row of decline. High-tech finished goods imports were robust, but a fall in imports of basic raw materials, such as such as copper ores and electronic components, pulled the overall figure down. The overall decline in imports seems to reflect weak consumer spending and weak business sentiment.

Also watch out for trade sensitivities. The August surge in China’s exports included a 20% jump in shipments to the US as China’s imports from America only increased by 1.8%. This could lead to a response from the White House in the run-up to the November presidential election.

At least, though, we could be a little closer to unravelling the China polyester value-chain mystery I discussed on Monday.

But in my view, it is impossible to conclude from all the data that China’s economic recovery is on solid ground. In fact, on balance it seems to be on very shaky ground. This matters more than just about anything else for the global petrochemicals business, as China accounts for around a third of global demand across all the products – more than any other single country or even region.