By John Richardson

OH DEAR. The global polyethylene (PE) industry is in as deep trouble as the global polypropylene (PP) industry (PP was the subject of my 8 February blog). Today’s three charts on PE will confirm this.

I believe one of the reasons why these two industries are in such a state is Chinese demand growth being lower than the consensus view.

In 2021 and 2022, widespread expectations were for high single digits growth across most of the grades. This, I believe, helped justified investment in many tonnes of new capacity.

But I had long warned that China’s growth would eventually fall short of expectations because of structural problems with the local economy. From September 2021 onwards, I flagged up that the “eventually” had arrived.

The downturn in growth in 2021 and 2022 was then made worse by the zero-COVID policies.

China, of course, matters so much because in 2022 it accounted for 33% of global consumption of PE – way more than any other region. Its 2022 share of global PP demand was much higher at 42%.

But China must not be the whole story. In one of my global PE scenarios below, I wipe off the disappointment of 2021 and 2022 and imagine Chinese consumption growth of 10% per year from 2023-2025, and yet overcapacity remains at record highs.

Perhaps too many project proponents overestimated demand growth in the developing world ex-China, on the mistaken idea that the region was rapidly becoming middle class by Western standards.

True, 2020 was a bad year for the developing world ex-China because of the pandemic. But most of the lost demand was recovered in 2021 and 2022.

Further, in the mature markets, demand for PE improved during the pandemic because of more eating at home and less in restaurants, all the packaging needed for the surge in durable goods consumption and increased medical and personal protective equipment needs.

So how exactly we got in this mess I am not sure. Maybe another reason was that not all the project backers were aware of all the other projects.

But what is clear is that we are in a historically deep mess.

ICIS base case for the 2023-2025 global PE supply and demand balance

Now let’s focus on today’s charts on PE, starting with the ICIS base case for global PE demand versus capacity.

China’s PE demand in 2022 declined by an average of 1% across the three grades compared with the previous year.

We have recently increased our forecast for this year’s growth to a 5% average from an earlier prediction of 3%. ICIS expects 4% growth in each of the years 2024 and 2025.

The ICIS base case also sees strong growth in the other regions. For instance, we expect 7% growth this year and 6% in each of 2024 and 2025 in Developing Asia and Pacific for high-density PE (HDPE) and linear-low density PE (LLDPE).

Developing Asia and Pacific does not include the developed economies of Australia, New Zealand and Singapore. I treat these three countries as a separate region.

In no region do we see growth as negative for any of the three grades in 2023-2025, even including the Former Soviet Union.

Nevertheless, we are forecasting that PE capacity exceeding demand will be at 25m tonnes this year and will average 24m tonnes per annum in 2023-2025. This would compare with an annual average of 10m tonnes/year in 2000-2022.

This year’s operating rate is forecast be at 79.5% versus the 2000-2022 annual average of 85.6%. Under this base case, global demand growth would be 3.4% in 2023 and at 3.3% in each of 2024 and 2025.

Scenario Two

As I said, our base case for China’s growth already factors in a strong recovery. So, in my second scenario, the first of two upsides, I stick with our base case for China.

I cannot realistically see China growing any more than our base case. And growth of around 3% this year, and something similar in 2024 and 2025, seems more likely to me.

But for every other region, except the Former Soviet Union for obvious reasons, I have raised our base case growth by one percentage point per year for each of the years from 2023 until 2025.

Under such an outcome, cumulative global demand in in 2023-2025 would be 2.2m tonnes higher than our base case, with this year’s operating rate edging slightly higher to exactly 80%.

Global demand growth would be at 4.1% in 2023 and at 4.1% in 2024 and 2025.

But capacity exceeding demand – assuming the same capacity additions as the base case – would be at 24m tonnes in 2023 and at a 2023-2025 annual average of 23m tonnes.

As we estimate annual capacities based on staggered start-ups (for example, we may only allocate 200,000 tonnes/year of a plant’s nameplate capacity of 350,000 tonnes/year in the first year of operations), bleak market conditions might mean lower 2023-2025 capacity additions than what we have assumed.

But nearly all the plants we have listed for start-ups in 2023-2025 must be either completed or close to completion. And why delay start-ups when debt repayments are due to kick-in on locked-in dates, no matter how bad the margins?

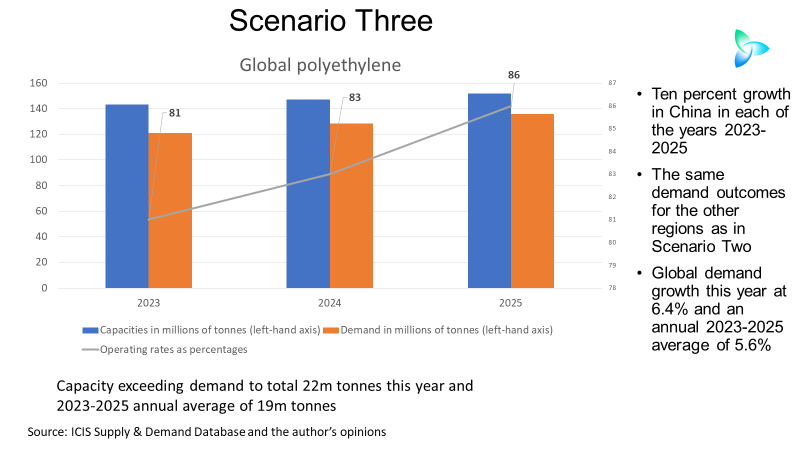

Scenario Three

I see Scenario Three as extremely unlikely. But for the argument’s sake, I increased China’s growth to 10% during each of the years from 2023 until 2025.

I kept growth in the other regions the same as in Scenario Two, while also maintaining our base case for capacities.

The end-result is this chart:

Global operating rates would be much healthier, with 2023-2025 cumulative demand 7.7m tonnes more than our base case. Global demand growth would be at 6.4% in 2023 and at annual 5.6% average in 2023-2025.

Here’s the thing, though: Global capacity would still exceed demand by 22m tonnes in 2023 and would be at an annual average of 19m tonnes in 2023-2025!

Just to underline how unlikely this upside is, in no year between 2000 and 2021 was China’s PE demand growth at double digits in more than two consecutive years – and this includes the one-off real estate-fuelled boom years of 2009-2021.

Between 2000 and 2022, global demand growth was at annual average of 4%. In other words, 2023-2025 would have to be statistical outliers to hit a 5.6% average. This seems unlikely given the extent of the economic challenges.

Conclusion: The danger of consensus thinking

If you went with the crowd in believing that China’s PE demand growth could never dip below an average of 5% per year, this might be one of the reasons you are in trouble.

But those who were with me in forecasting the China slowdown could be in better positions. It was clear from as early 2014 that the 2021-2022 slowdown would have to happen at some point.

You might have also been drawn to the crowd’s other mistaken idea that the developing world ex-China was booming as it became middle class by Western standards. Did this lead to you overestimate the region’s consumption growth?

And/or did you more simply just miss many of the new projects that are coming on-stream in 2023-2025.

As I said earlier, none of us are likely to ever know the exact reasons why we are where we are today.

But what this crisis tells us that following the crowd isn’t always a good idea, as the crowd can often miss the wider political, social and economic context.

Quite often, also, the crowd misses what the data is really telling us because of collective wishful thinking.