WHEN stock markets are rising it makes sense to fund your investments through margin debt. Over the last ten years in particular, this approach has produced stellar results because of the abundance of cheap and easy finance.

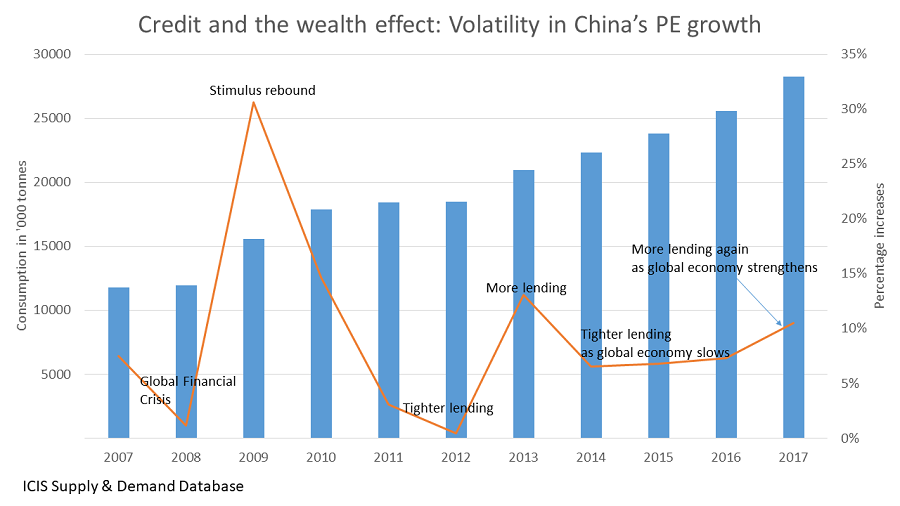

But the above chart is an example of what can happen when lending tightens and demand for margin debt declines. The reversal of fortunes that has already happened in China could soon be mirrored in US stock markets, as I shall discuss in my post on Wednesday.

As of today (Monday), China’s stock markets have gained some of their lost ground following comments by Liu He, top economic adviser to President Xi Jinping, who has sought to boost confidence in the country’s economy, stock markets and broader reform programme.

But I believe we are close to the end-game of the post-Global Financial Crisis credit bubble.

Confidence begets more confidence

It began back in late 2008, when Ben Bernanke’s zero interest rate and quantitative easing policies led to a search for yield amongst investors. This resulted in money pouring into emerging markets. As share prices moved up, local confidence rose because shares were worth more. The banks allowed investors to borrow more as the value of holdings had gone up.

But then the US Federal Reserve began to raise interest rates at the same time as Donald Trump started his trade war with China – and at the same time as China began to cut back on the availability of lending across the whole of its economy in order to tackle bad debt issues.

From a virtuous to a vicious circle

Some foreign investors started selling because they saw better opportunities back at home. Local investors couldn’t roll over their loans because of tighter domestic liquidity, including a big clampdown on peer-to-peer lending. This meant that they too had to start selling. So the market began to slide.

The virtuous circle turned vicious as underlying values fell. People had to either put up more cash or sell. Then panic started to set in. Fear rather than greed began to dominate and everyone wanted to get out asap. Lenders dumped the stock that they had been holding as security for their money.

That was the story up until last Friday by which time the Shanghai Composite Index had fallen to a four-year low. As Bloomberg wrote:

With $603 billion of shares pledged as collateral for loans, or 11% of China’s market capitalisation, one concern is that forced sellers will tip the market into a downward spiral.

This is an echo what happened in mid-2015 during a similar collapse in Chinese equities. Back then the central government stepped into rescue the stock market – and also embarked on a renewed wider economic stimulus programme that re-inflated the housing market. The lost wealth effect from equity losses was replaced by gains on real estate.

This time around, though:

- A new S&P report suggests that China’s government may not have the financial capability to launch another big economic rescue package

- The global environment is much more hazardous to China than in 2015 because of the trade war – and because, as I again shall discuss on Wednesday, a similar end-game could be about to play out in US stock markets.

The effect on petrochemicals demand

The above chart is an important reminder of the very volatile nature of growth in one polymer – PE – since 2007. The same applies to all other petrochemicals and polymers.

It is the wealth effect in China that has mainly driven the extraordinary growth in PE demand since 2007 – up by 140% between that year and 2017. It cannot be income growth alone, as the rise in average incomes has been much more modest than the rise in personal wealth.

A major risk is that the weakness in China’s stock market spreads to the broader economy for the reasons I’ve just detailed above, with the impact on the housing market of great importance. The housing market is a bigger store of wealth in China than equities.

In 2008, Chinese PE demand grew by just 1%. Let’s assume the same happened in 2019 compared with our base case of a 5.3%. The end-result be 1.7m lower growth in PE demand.