By John Richardson

AHA! I had another of those light bulb moments yesterday after a dozen or so calls, including one to our excellent ICIS pricing team in China about why, despite deep China operating rate cuts, we have ended up with the above chart.

This is a question I’ve been pondering for the last week. Why, despite rate cuts on a scale many people have never seen before, did polyolefins spreads (the gaps between the prices for tonnes of resins versus costs for tonnes of naphtha) decline in March rather than increase?

If you look closely at the chart, you will see spreads in all the grades –- except low-density polyethylene (LDPE) – reached their lowest levels in March since our price assessments began in November 2002.

In the case of polypropylene (PP), this article from my ICIS colleague Lucy Shuai details how Chinese producers announced rate cuts in March, including idling whole units, that were equivalent to 24% of the country’s total capacity.

Yes, 24% and yet in March, the spreads between CFR China PP injection grade prices and CFR Japan naphtha costs fell to $201/tonne from $267/tonne in February.

Rate cuts of a similar scale are reported to have occurred in PE, but, again, spreads declined in March over February.

The most dramatic polyethylene (PE) decline was in high-density PE (HDPE) injection grade to just $98/tonne in March from $203/tonne in February. February this year was the previous record-low spread since November 2002.

Market participants had expected spreads to increase in March as supply and demand were brought more into balance.

But as one contact said: “There is hardly any demand because of the lockdowns. Truck drivers are not available to pick up resins from the polyolefins plants, some of the converters are not operating, and end-use demand has pretty much cratered”.

Reductions in production at naphtha-based and other liquids-feed based cracker-to-polyolefins plants – which are mainly located in China’s richer eastern and southern coastal provinces – seem to have been forced by the logistics and demand challenges.

It is worth noting that China’s smaller coal-based polyolefins capacity hasn’t seen extensive rate cuts.

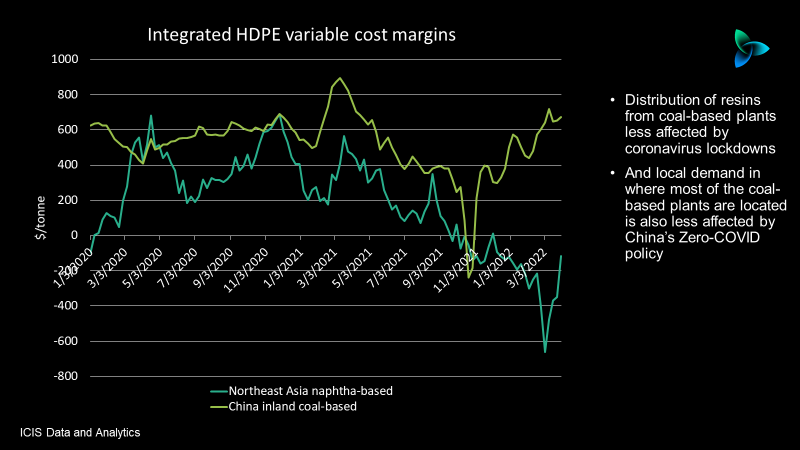

This appears to be because the plants are mainly located away from the big outbreaks of Omicron – and because coal-based margins (different from spreads, of course) are better than naphtha-based margins, as the chart below illustrates.

The margins appear to be better because of the rise in oil and so naphtha costs relative to coal – and because the local markets served by the coal-based plants are less affected by the lockdowns.

The chart only shows inland China HDPE coal-based integrated variable cost margins versus northeast Asia (the same as China) HDPE naphtha-based integrated variable cost margins. But the patterns are similar in the other products.

What was surprising about the rate cuts was that China normally runs its petrochemicals plants hard, even at times of poor profitability, in order to keep people in jobs in downstream factories.

But as logistics appear to be hindering distribution of resins, with some finished-goods factories reportedly closed due to China’s Zero Zero-COVID policy, this round of rate cuts seems to have been very different.

High-frequency data points could be presenting the real economic picture

As always in China, separating the official views from what might be really happening on the ground is critically important.

“One tally put the lost productivity from China’s patchwork of COVID lockdowns at nearly $50bn a month, using reductions in trucking traffic to estimate the losses,” wrote Quartz in this article.

Authorities had tried to ease the impact by allowing ports, factories, and some offices to have their workers live at work sites, added the investment news and analysis site.

But strict border rules, including lengthy quarantines, had damaged China’s aviation and tourism industries, said Quartz.

“While China maintains port operations are continuing as normal despite the lockdown, a supply chain tracking firm says ocean shipment volumes have been reduced,” the article continued.

The number of ships awaiting a berth in Shanghai and the nearby port of Ningbo had increased. according to data from Kuehne+Nagel International AG, a Switzerland-based global logistics operator, quoted by the Wall Street Journal.

Around 100 vessels were waiting to dock on Monday [(4 April), up and from 62 on 1 January this year, the newspaper reported.

Similar discrepancies between official views and data points versus what could really be happening were highlighted by The Economist in this article.

“The most recent hard numbers on China’s economy refer to the two months of January and February. Those (surprisingly good) figures already look dated, even quaint,” wrote the magazine.

Most of February was, of course, before the Russian invasion of Ukraine and before the big surge in China’s Omicron cases. The inflationary impact of the invasion is further damaging China’s economy.

The Economist quotes data from Baidu, a popular search engine and mapping tool. Based on Baidu’s tracking of smartphone movements, during the seven days to 3 April, the index was more than 48% below its level a year ago.

During the week ending 2 April, the number of metro journeys in eight big Chinese cities was nearly 34% below its level from a year ago – and 93% down in Shanghai, The Economist added.

Ting Lu, an analyst with Nomura, was quoted by The Economist as warning that the short history of this type of high-frequency data raised questions about its reliability.

But he added that most these types of data were pointing in the wrong direction – normally an indication of problems with GDP growth.

And we mustn’t forget the property market, the source of most of China’s tremendous petrochemicals demand growth from 2009 until 2021.

The market continues to deflate because of China’s Common Prosperity policy shift.

“China’s home sales slump deepened in March, keeping pressure on cash-strapped developers even as policy makers vow to support the property market,” wrote Bloomberg in this article.

The 100 biggest companies in China’s debt-ridden property industry saw a 53% drop in sales from a year earlier, according to preliminary data from China Real Estate Information Corp, the wire service added.

What is also important to note is that most of China’s polyolefins demand is concentrated in the richer coastal eastern and southern provinces, where Omicron lockdowns are also concentrated and where most of the property boom took place.

The chart below only details HDPE, but it is the same pattern in the other resins.

Beijing may have lost control of events

Nomura, in its 1 April podcast, said that the worst stage of China’s downturn would be reached this Spring.

But the bank importantly added: “We do not view inflation as a barrier to Beijing launching more supportive policy easing and stimulus measures in 2022.”

The South China Morning Post, in this article, wrote that more than 60 municipal authorities would introduce easing measures designed to re-inflate the real-estate sector.

And we were in this place two years ago, in April 2020, when all looked doom and gloom. But China enjoyed nothing short of a H2 2020 economic boom.

But as far as China’s export trade is concerned – the reason for its H2 2020 economic boom – this time feels very different.

Western governments cannot launch stimulus on the same scale as in 2020 because of higher interest rates.

It was this stimulus that gave bored lockdowners the money to spend on mainly Chinese-manufactured durable goods.

The inflation crisis in the West, along with further supply-chain disruptions caused by the Ukraine-Russia conflict and China’s Zero-COVID policy, may further jeopardise the chances of a China export-led recovery.

And however sensitive this issue is, it cannot be ignored: China’s close relationship with Russia means it is at risk of secondary sanctions.

Could Beijing have lost control of events? Is its successful track record of always lifting the economy out of temporary slumps through effective countermeasures under threat?

I feel, yes, this is a scenario that needs to be considered because we have rarely, if ever, faced so many economic challenges at the same time.

Nobody has any idea on how long it will take China to bring its latest coronavirus outbreak under control, with the Zero-COVID policy perhaps its only option because of reports of the lack of effectiveness of Chinese vaccines and low vaccination rates among the elderly.

Further, will China want to go for major economic stimulus later this year as this would run counter to its essential Common Prosperity economic reforms?

At the very least, the poor start to the year means that, even with a much stronger H2, China’s polyolefins demand growth is going to struggle to hit consensus forecasts of the high single digits.

Please, please be careful out there and adjust your operating and sales plans in response to these risks.