By John Richardson

The only honest answer is that none of us know how events will turn out because of the rapid pace and unpredictable nature of the coronavirus crisis. As of writing, for instance, India had just gone announced a temporary lockdown

But petrochemicals companies must still try and predict the future otherwise they cannot set revenue targets and operating rates. Normal business life must go on.

What follows is therefore an attempt to portray the facts as I see them now. I present two scenarios for when the crisis might be brought under control. I will update this document every week.

The best-case outcome is the crisis is brought under control within six months. This would involve using a global programme of suppressions (complete lockdowns) followed by mitigations (partial lockdowns) and existing drugs.

Suppressions as a standalone solution may not work because of the risk of secondary outbreaks when quarantine restrictions are lifted.

This is the risk facing China. Medical experts are warning that because not enough of the Chinese population have caught and recovered from the disease, the population’s immunity may not be strong enough to prevent another major outbreak.

Mitigations are also by themselves risky as the disease could run out of control and health services, even in developed countries, could become quickly overwhelmed.

The best approach might thus be suppressions that bring the disease out under control followed by mitigations that gradually allow those who’ve recovered from the disease out of quarantine.

But note that the economic shocks of suppressions are huge. China’s GDP for example fell by an astonishing 10-20% in January-February – the biggest decline since the Mao era.

Big data may help process all the data points necessary to constantly improve and enforce monitoring systems. We are in a vastly better position to achieve this than in 2003, during the SARS outbreak, because of developments in information technology.

But there is a risk of sick people dodging even the best monitoring systems, especially in the West where this is an inherent mistrust of governments. During times of extreme crisis, though, democracies can knuckle down. A good example was Britain during the Second World War.

Getting enough existing drugs out into the community rapidly enough (a new vaccine is thought to be at least a year away) would require the drugs to be first of all clinically approved – and we are not there yet, although there are some hopeful signs.

The drugs would also have to be distributed on a scale and at a cost sufficient to stop the disease in its tracks.

This might also require a wartime production footing for pharmaceutical companies if existing supplies are not enough and a willingness to distribute drugs at low cost. There would need to be a quick resolution of global shipping problems.

All the above would require strong political leadership and levels of global political cooperation close to what occurred in World War II. Several of today’s world leaders do not inspire me with confidence.

But humans are capable of remarkable things when they put their minds to it. Perhaps our political leaders, no matter what their previous track record, will step up to the plate. If governments everywhere forget their differences, we might achieve the levels of cooperation needed.

Worst-case outcomes include a prediction from the Robert Koch Institute, which sees the disease taking a further two years to bring under control. It warns of years of extreme suppressions followed by mitigations (several waves could be necessary) until a vaccine can be made, tested and put into use.

The impact on petrochemicals demand

What follows is an attempt to support demand forecasting, using ethylene as an example – the biggest of all the petrochemicals building blocks. I hope this will support discussions about future revenues and restructuring plans (the way things stand today, and let’s be realistic, new capacity investments must be postponed or cancelled).

Before I start, one important point on demand is in my view this: It is simply impossible that panic buying of food and other daily necessities will mitigate the impact of the demand loss from this crisis. There appears to be a H1 boost to polymers consumption resulting from panic buying. But to me it is clear that:

- This is just a big restocking and destocking process where demand for polymers used in packaging is being brought forward from a later date.

- Even in the best-case outcome – as mentioned above, the disease being brought under control globally within the next six months – the loss of polymers consumption from the collapse of other economic activity will be greater than temporary gains from restocking.

- Huge global economic stimulus programmes will make a major difference when most people are back in their offices and at school. A major positive is the scale of these rescue programmes. But meanwhile, it is very difficult to stimulate economic activity that’s not taking place

What follows on global ethylene demand will be wrong as is this just a guesstimate. But I hope it will help give your internal discussions a framework.

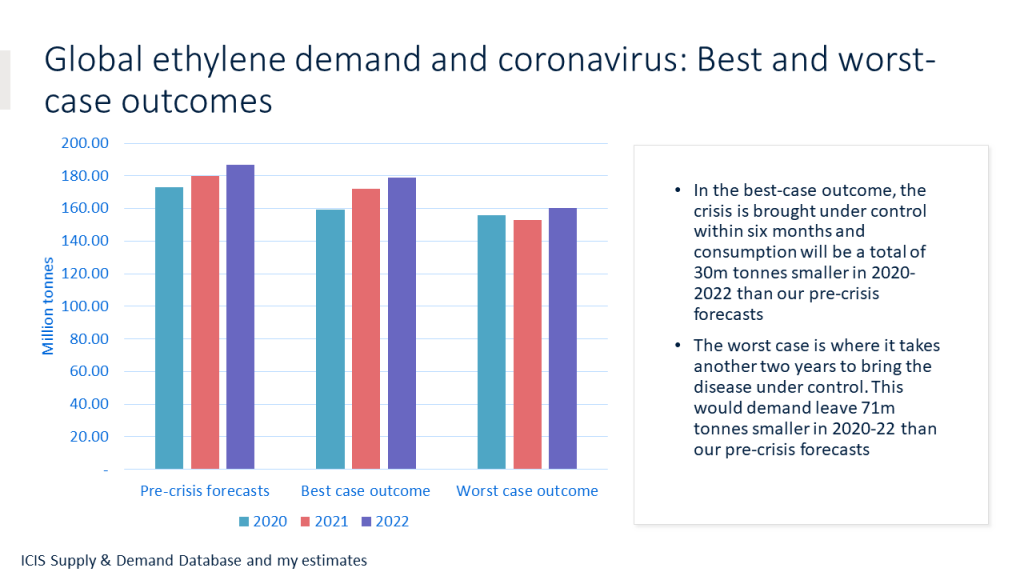

The above chart which assumes the following:

- In the best-case outcome – getting on top of the crisis within six months – global ethylene demand growth falls to minus 4% in 2020 versus last year. This would be double the minus 2% growth we saw in 2008 during the Global Financial Crisis, as this is a more severe economic event than 2008-2009. Growth then jumps to 8% In 2021 because of huge global economic stimulus, followed by growth of 4% in 2022 (our pre-crisis forecast had assumed growth at 4% during each of the years from 2020 until 2022). This would result in consumption being 30m tonnes smaller in 2020-2022 than our base case.

- The extreme outcome – the Robert Koch Institute worst-case scenario p would lead to minus 6% growth this year, minus 2% next year and positive growth of 5% in 2022 as the global economy recovers in the second half of 2022. The 2020-2022 loss of demand versus our pre-crisis forecast would be 71m tonnes.

Other scenarios are possible between these two extremes.

Conclusion

We are in this together as a business community. We can and will come through this and emerge from the other side in a stronger and more resilient position.

Think of this: We have the best online tools we have ever had. This will enable us to communicate with each other in ways that would have been impossible just a few years ago. In today’s virtual world Microsoft Teams and Skype calls etc. are a good substitute for face-to-face meetings.

We can move forward by sharing data, ideas, theories and market intelligence as we assess what the outcomes will be for our industry. ICIS is part of this debate. For more information on how we can help through free Webinars etc. please contact me at john.richardson@icis.com