See below my review of China’s linear-low density polyethylene (LLDPE) market in 2021 with some further thoughts about what could happen during the rest of this year. This follows my earlier reviews and outlooks for high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and polypropylene (PP). I shall complete the series next week when l will cover low density polyethylene (LDPE).

By John Richardson

CHINA’S LLDPE demand grew by just 1% in 2021 over the previous year, I believe. This would be the third-lowest rate of growth since 2000.

My latest forecast is slightly better than my earlier expectations of flat or zero growth. But 1% growth is against other forecasts of around 8%.

Last year was always going to see a growth deceleration because 2020 was a “bubble year”.

During 2020, China exported itself into a strong recovery from the pandemic as it provided most of the goods the West wanted or needed during lockdowns. This led to LLDPE demand in 2020 rising by 13% over 2019.

What also contributed to the 2021 slowdown from August onwards was the Common Prosperity policy shift.

This involved a deflation of the property bubble, leading to less LLDPE demand linked to real estate. Think of all the packaging for the carpets and washing machines etc that furnish new homes that were no longer required as home sales fell.

Also consider the decline in discretionary consumer spending as the growth in personal wealth slowed down due to the government’s deleveraging of real estate. Less discretionary spending again led to less demand for LLPDE used for packaging.

China introduced new restrictions on the use of single-use plastics in early February 2020, just before the pandemic.

The restrictions were put on hold because of the pandemic but were enforced last year, I’ve been told. This would again fit in with Common Prosperity as another of its objectives is cleaning up the environment.

The chart below, however, also includes the important context of 2019 – a “pre-bubble year”. LLDPE demand in 2021 still grew by an extremely healthy 14% over 2019 – an extra 1.9m tonnes of demand.

China’s LLDPE imports fall by 17% year on year in 2021

The context is again important here because of the distorting effects of a bubble 2020. The second half of that year saw a surge in Chinese imports – the “China in, China out” story as imports rose to package the surge in demand for China’s exports of finished goods.

This meant that, as with LLDPE demand, a decline in imports was inevitable in 2021. The decline by 17% year on year in 2021 needs to be put into the context that versus 2019, last year’s imports were only down by 3%.

It is important to note, however, that Chinese capacity increased by 14% in 2021. The latest ICIS estimate is that last year’s local operating rate was at an average of 93%, significantly higher than the 88% that we forecast in the ICIS Supply & Demand Database.

This points to risks ahead for global producers and opportunities for buyers, as I shall discuss next.

LLDPE exporters’ exposure to China: getting as close as possible to the bullseye

ICIS LLDPE data is pure gold dust. Each data set, along with the context, moves us closer towards the bullseye of the proverbial dartboard – credible scenarios for what’s going to happen next.

Let’s start with the chart below. In tonnes rather than millions of tonnes in order to make it easier to study, it shows the volumes China recorded as imports from its top 10 LLDPE trading partners in 2021. These tonnes are then compared with the tonnes recorded for 2020 and 2019.

As you can see, Thailand was the only country that lost ground throughout 2019-2021 and South Korea the only country that gained market share during the whole period.

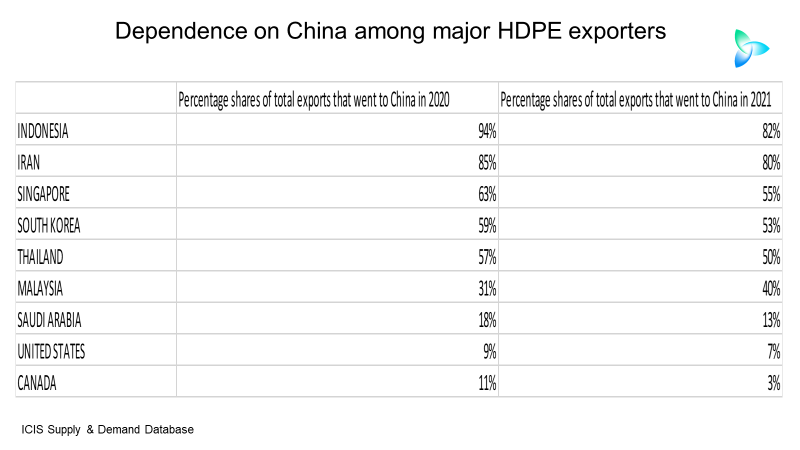

Let’s look at the trade data from another angle – the percentage of export dependence of these countries on China. Note that we don’t have the data for the United Arab Emirates.

Indonesia, Iran, Singapore, South Korea and Thailand remained the most exposed to China in 2021 versus 2020.

Important context here is that Indonesia is a net importer. Its small volume of exports mainly went to China because of the ASEAN-China free trade deal.

Iran, Singapore, South Korea and Thailand are major net exporters, with again Singapore and Thailand’s exports supported by the ASEAN-China free trade deal (the same, of course, applies to Malaysia).

We must next consider LLDPE capacity expansions in 2022. South Korea’s capacity is forecast by ICIS to increase by 8% over last year to 2.4m tonnes/year.

And, much more importantly, we estimate that China’s capacity will increase by another 9% in 2022 to 11m tonnes/year.

I believe that because the Common Prosperity policy pivot will continue – and because China’s Zero COVID policy will last until at least October or November when a major political meeting is due to take place – this year’s LLDPE demand growth will remain weak.

Combine this with what I see as high local LLDPE operating rates because of China’s push towards greater self-sufficiency, and the result is the chart below, first published in a blog post in January.

The chart shows my two alternative outcomes for China’s net LLDPE imports in 2022 versus the ICIS base case for China and the ICIS base case for the other net import countries and regions.

Even under my Downside 2 scenario, China would completely dominate global net imports among all the countries and regions that are expected to import more than they export.

Conclusion: dealing with challenges and opportunities

Unless you’ve been analysing the earth’s LLDPE market from Mars, you should be aware by now that in 2000, China accounted for just 15% of global demand. In 2022, this had risen to 36%, way ahead of any other country or region.

So, calling all producers: you need to follow the minutiae of Chinese demand and, as I’ve also demonstrated, every tiny shift in Chinese supply. You must hedge your risks.

For buyers, the opportunities remain big from what I see as an eventual “great deflation” – the equalisation of global pricing more towards today’s Chinese levels.

This may not happen this year because supply chain constraints are dragging on and on.

As always, what you’ve just read only scratches the surface. For more information on how ICIS data and analytics can support your planning process, contact me at john.richardson@icis.com.