By Paul Hodges of International eChem

Two months ago, very few people believed that markets were about to tumble. But on 18 August we published our Great Unwinding analysis. Since then, its forecasts have begun to come true, as the impact of policymaker stimulus begins to unwind.

Oil and commodity prices are falling sharply as supply/demand once again becomes the key driver for prices; the US dollar is strengthening and liquidity is tightening across the world; equity markets risk sharp falls, as investors realise they have overpaid for future growth and rush for the exits; China’s economy is slowing fast as the new leadership implements the World Bank’s ‘China 2030’ plan; interest rates are becoming volatile as some investors seek a ‘safe haven’, while others worry that stimulus policy debt may never be repaid.

Of course, many believe this is just a long-overdue correction rather than a complete change of direction. They argue it is 1000 days since US financial markets suffered a real reverse. And so, in their view, this is just ‘the pause that refreshes’ the bull market.

But what if this rosy view is wrong, as we argue in our new report, ‘The pH Report’?

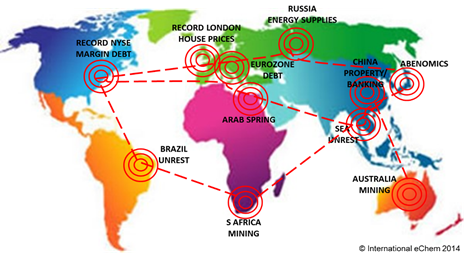

Our recent discussions with investors have highlighted a growing concern that many of the key challenges facing the global economy may be far more connected than currently recognised. As the map above shows, a common thread of debt links developments in China, Japan, the eurozone, South Africa and Australia. Today’s record levels of London house prices and margin debt in US financial markets are also increasingly being linked with recent central bank policies, all focused on stimulating consumer demand.

Investors are beginning to worry that they are missing the bigger picture, which connects the dots for all these issues. Was it really the announcement of a possible Fed tapering last year that has since created major tremors in a wide arc of emerging economies from Brazil, through south east Asia, the Middle East and Russia? Or are they linked together in some other way, which is yet to become apparent?

The China syndrome Everyone remembers the old joke, ‘Why did the elephant wear dark glasses?’, and the answer, ‘So that she wouldn’t be recognised’. A more modern version might be: ‘Why did nobody notice that China was the “elephant in the room”, the main cause of today’s downturn in global demand and financial markets?’ Answer: ‘Because we were all wearing rose-tinted glasses’.

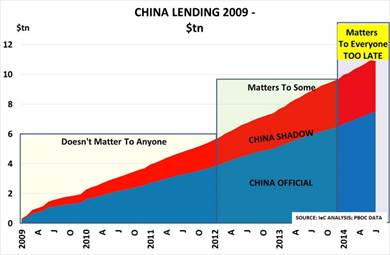

From 2009, China’s boom stabilised the global economy. But it was based on the largest debt bubble in history, with lending up from $1tn in 2008 to $10tn in 2013. Since the new leadership was appointed in 2012, our rose-tinted glasses have made us want to believe that another major lending programme was just about to be announced. But every month, ever-clearer signals come from Beijing confirming that new stimulus is the last thing on their minds.

Thus premier Li Keqiang caused unprecedented walk-outs during his welcome address to the Summer Davos meeting in Tianjin last month, when he announced:

“There’s already a lot of money in the pool, and we can’t rely on monetary stimulus to spur economic growth… Facing the New Normal state of the Chinese economy, we have remained level-headed and taken steps to tackle deep-seated challenges… in the latter half of the year and beyond, we will accelerate the transformation of the development model.”

Now the Unwinding is underway, we can expect a painful period of structural adjustment to begin. The reason is that the volume of stimulus has been so large, and so widespread, that it has overwhelmed the critical role of price discovery in many markets.

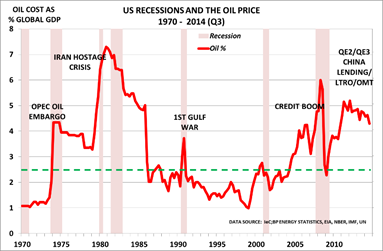

Oil prices have been too high, for too long

More recently, it has become apparent that our rose-tinted glasses were in fact bi-focal. Without them, we would have long ago recognised that oil prices have accounted for around 5 per cent of global GDP since 2011 – the longest period since the early 1980s. And we would have noticed, as the chart reminds us, that every sustained period of prices at this level has led to recession in the past.

Instead, we took comfort in the belief that ‘this time was different’. But in reality, the seeming stability of oil prices around the $100 a barrel level was not due to a unique combination of exceptional demand growth and unprecedented supply shortages. Instead, there is growing evidence that it was driven by a combination of temporary demand created by China’s massive stimulus programme, and the flood of low-cost money from the central banks.

Between them, these two influences appear to have broken the price discovery process. How else can one explain the fact that, as the International Energy Agency noted in August, “Oil supplies were ample, and the Atlantic market was even reported to be facing a glut”? Or that more recently it has warned that “the recent slowdown in demand growth is nothing short of remarkable.”

Increasing numbers of investors are thus now struggling to understand why oil prices have been so high for so long, especially as the economic news looks more troubling. Recession risks are haunting Germany as well former Bric power-houses Brazil and Russia, while China is slowing fast.

This confirms the concern identified by new US Federal Reserve deputy chairman Stanley Fischer at August’s Jackson Hole meeting: “Year after year we have had to explain from mid-year on why the global growth rate has been lower than predicted as little as two quarters back”.

How does this story end?

Nobody knows how the Great Unwinding of central bank stimulus policies will develop.

Policymakers have chosen to believe that printing money can compensate for the inevitable slowdown in demand caused by today’s globally ageing populations. But as the Great Unwinding of these policies takes place, will we instead discover they have unintentionally created a debt-fuelled ‘ring of fire’ with multiple fault-lines?

As the FT’s John Plender began a recent article: “In a market where asset prices are comprehensively rigged by central bankers, rational investment becomes impossible. Discuss.”

Paul Hodges is chairman of International eChem, a London-based strategy consultancy, and co-author of “Boom, Gloom and the New Normal”.