By John Richardson

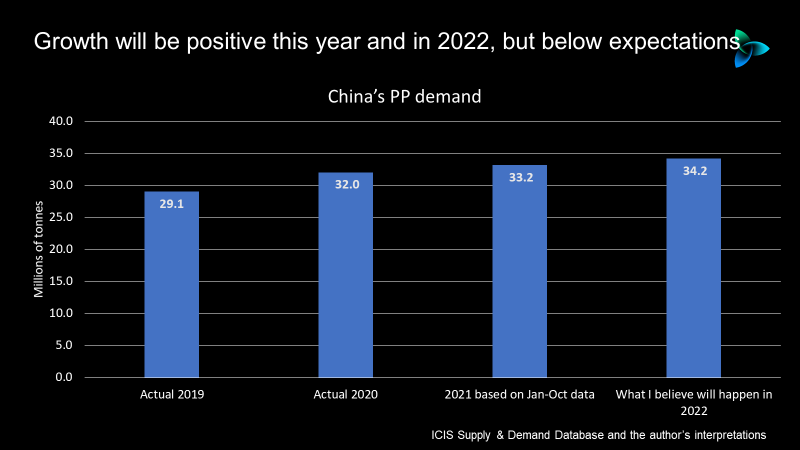

LET’S PUT THIS in perspective. Yes, as the chart below indicates, China’s polypropylene (PP) demand growth in 2021 is in line to be disappointing relative to what I have long seen as over-bullish expectations. But, unlike in polyethylene (PE), year-on-year PP demand growth will still be positive.

Over-bullish expectations are persisting into 2022 because not enough consideration is being given to the monumental changes in the Chinese economy that will result from the Common Prosperity policy pivot.

Now let’s go through this chart in detail.

I think demand will increase by 4% this year versus other forecasts of 8-9%. The more upbeat forecasts assume this year will be similar to 2020, when actual demand rose by 9% over 2019.

But 2020 was a “bubble year” because of “China in China out”, the boom in H2 imports and local demand resulting from the pandemic-related surge in China’s exports of finished goods. As I warned late last year, a cooling-off in growth seemed inevitable and this has happened in 2021.

Next year, I expect a growth of 3% – again lower than other estimates of 5-6% I am hearing from market participants.

I see long-term growth decelerating from historic trends because of lower overall GDP growth and the push to make economic expansion less commodity intensive, because Common Prosperity will continue.

Common Prosperity will continue because the political groundwork has been laid for Chinese president, Xi Jinping, to remain in office until as late as the early 2030. With political stability will come policy stability.

A lot of distracting noise was generated by yesterday’s announcement that China would reduce the reserve requirement – the amount of funds the banks must set aside against their landing. This is the second cut in 12 months and will give banks more flexibility to lend money.

This comes along with other measures aimed as stabilising the economy in response to the negative hit from Evergrande and the deceleration of the property sector.

“Everything is back to normal – the China boom is back on!” was a WhatsApp message I received from a contact following the decision on the reserve requirement.

No. As I said, overall GDP growth will moderate as the extra fizz from excessive real-estate speculation is removed from the economy. This must happen because housing oversupply is leading to worrying levels of debt. The property-driven growth model has run out of road.

Each percentage point of GDP growth rate over the next 20 years will be less commodity intensive for environmental reasons, as China hits its C02 emissions-reduction targets and builds vast new job-creating green industries.

These new industries will, I believe, help China escape a middle-income trap made deep by a rapidly ageing population.

Another negative factor for polymers growth is China’s big push to reduce the consumption of single-use plastics as it potentially builds a world-beating state-of-the-art recycling industry. Such an industry would also help its escape from the middle-income trap.

Common Prosperity could go wrong, of course. It could fail with no return to the old growth model possibly because, as I said, it has run out of tarmac.

But I don’t see this happening because of China’s great track record in managing its economy extremely well. Still, though, please plan for a worse downsidr as opposed to my moderate downside.

In detail, my moderate downside assumes the following:

- Demand at 33.2m tonne this year, as mentioned earlier 4% higher than last year, against other forecasts of an 8% increase to 34.6m tonnes.

- A 3% increase in 2022 to 34.2m tonnes compared with other estimates of a 6% rise over the higher number. These more bullish predictions would result in next year’s demand reaching 36.7m tonnes. If my estimates are correct, this would leave 2021-2022 PP consumption 3.9m tonnes lower than the more optimistic projections.

This lower volume would significantly move the global demand needle in the wrong direction as China accounts for approximately 40% of global consumption. But even under my lower estimates, Chinese demand in 2022 would still be 2.2m tonnes higher than in 2020.

But my outlook for China’s PP imports – and also crucially net imports/exports – is far more gloomy.

China could become a net exporter by as early as next year

It looks as if China’s PP imports will total around 4.8m tonnes in 2021, which would be 1.7m tonnes lower than in 2020.

This year’s projected drop in imports is implied by the China Customs trade data for January-October (simply divide the number by 10 and multiply by 12 to get to a total for 2021).

The sharply lower imports are a clear pointer towards the deceleration of demand growth that I discussed earlier. They also reflect a 13% increase in local capacity to 34.9m tonnes/year compared with 2020. The ICIS estimate for 2021 operating rates is 86%.

Assuming operating rates remain at 86% in 2022, our projected further 11% increase in capacity to 38.9m tonnes/year and demand growth at 3%, next year’s imports would drop to just 800,000 tonnes.

BUT, and this is the huge BUT and the most important stastistic in this post: I now see China becoming a net exporter in 2022, as exports exceed imports for the first time in its history. This is a year earlier than my previous estimate of 2023.

January-October 2021 exports totalled 1.2m tonnes, up from just 425,000 tonnes for the whole of last year.

If you again divide January-October 2021 exports by 10 and multiply 12, you get a total of 1.4m tonnes for the year, considering the exact numbers. I assume exports will be at least the same in 2022, if not higher. Take the 1.4m tonnes away from imports of 800,000 tonnes and in 2022, China is in a net export position of 600,000 tonnes

Wow! As the final chart for today details, going back t 2012, this would be a huge, huge shift in global PP trade flows.

Conclusion: you’ve had plenty of time to adjust

The good news is that China accounted for only 43% of global net imports of PP in 2020 amongst the countries that imported more than they exported, according to an ICIS estimate. This makes the world’s PP import market considerably less dependent on China compared with PE. In PE, we estimate that China’s net imports comprised 66% of the global total in 2020.

Other major PP import markets include Europe, Turkey and Asia and Pacific with Africa offering great long-term potential to consume bigger volumes.

Any global producer who has been following the blog since 2014 should have diversified their sales to these other regions, as it became clear during that year that China would eventually become self-sufficient in PP. If you haven’t already made the necessary adjustments, there is no more time to lose.

But even for those who have made the necessary adjustments, China’s transformation from being the world’s biggest importer to being a significant exporter represents nothing short of a market revolution