Residential construction work in Qingdao, China. Government stimulus is unlikely to deliver the economic boost of previous years © Bloomberg

On the surface, this year’s jump in China’s total social financing (TSF) seems to support the bullish argument. TSF was Rmb5.3tn ($800bn) in January-February, a 26 per cent rise on 2018’s level.

By comparison, it rose 61 per cent in 2009 as the government panicked over the impact of the 2008 financial crisis, and 23 per cent in 2016, when the government wanted to consolidate public support ahead of 2017’s five-yearly Party Congress session, which reappointed the top leadership for their second five-year term.

The markets were certainly right to view both these increases positively, as we discussed here two years ago. But we also added a cautionary note, suggesting that 2017’s Congress might well be followed by a “new clampdown”, as Xi’s leadership style was likely to “move away from consensus-building towards autocracy”. This analysis seems to have proved prescient, and it makes us cautious about assuming that Xi has decided to reverse course in 2019.

Consumer markets are also indicating a cautious response. Passenger car sales, for example, were down 18 per cent in January-February compared with the same period last year, after having fallen in 2018 for the first time since 1990. Smartphone sales were also down 14 per cent over the same period. In the important housing market, state-owned China Daily reported that sales by industry leader Evergrande fell by 43 per cent.

There is little evidence on the ground to suggest that Xi has decided to return to stimulus to revive economic growth. Last month’s government Work Report to the National People’s Congress said it would “refrain from using a deluge of stimulus policies”.

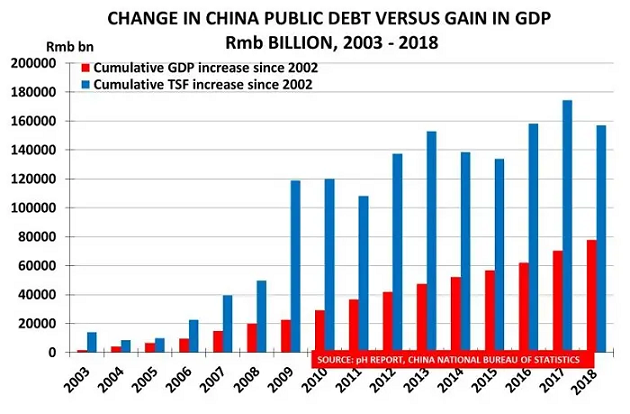

Instead, it seems likely that this year’s record level of lending was used to bail out local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) and other casualties of China’s post-2008 debt bubble. The second chart illustrates the potential problem, with TSF suddenly taking off into the stratosphere after 2008, when stimulus began, while GDP growth hardly changed its trajectory.

The stimulus programme thus dramatically inflated the amount of debt needed to create a unit of GDP. And given the doubts over the reliability of China’s GDP data, it may well be that the real debt-to-GDP ratio is even higher. These data therefore support the argument that debt servicing is now becoming a major issue for China after a decade of stimulus policies.

One example comes from the FT’s analyses of the debt problems affecting China Rail and China’s vast network of city subways. The FT reported that China has 25,000km of high-speed rail tracks, two-thirds of the world’s total, and that China Rail’s debt burden had reached Rmb5tn — of which around 80 per cent related to high-speed rail construction. Its interest payments have also exceeded its operating profits since at least 2015.

Unsurprisingly, given China’s relative poverty (average disposable income was just $4,266 in 2018), income from ticket sales has been too low even to cover interest payments since 2015. And yet the company is planning to expand capacity to 30,000km of track by 2030, with budgets increased by 10 per cent in 2018 as a result of the decision to boost infrastructure.

The same problem can be seen in city subway construction, where China accounted for 30 per cent of global city rail at the end of last year by track length, but only 25 per cent of ridership, which suggests that some lines may be massively underused and economically unviable.

The issue is not whether this level of investment is justifiable over the longer term in creating the infrastructure required to support growth. Nor is it whether the debt incurred can be repaid over time. Instead, the real question is whether the need to support economic expansion has led to a financially-risky acceleration of the infrastructure programme and whether, in turn, Beijing is now being forced to cover potential losses in order to avoid a series of credit-damaging defaults.

So where does this alternative narrative lead us? It suggests that far from supporting consumer spending, the TSF increase is flagging a growing risk in Asian debt markets — where western investors have rushed to invest in recent years, attracted by the relatively high interest rates compared with those enforced by central banks in their home markets. In 2017, for example, Chinese borrowers raised $211bn in dollar-denominated issuance, at a time when corporate debt levels had already reached 190 per cent of GDP.

This risk is emphasised if we revisit our suggestion here at the end of last year, that data for chemicals output — the best leading indicator for the global economy — was suggesting “that we may now be headed into recession”. More recent data give us no reason to change this conclusion, and therefore highlight the risk that some Chinese debts may prove more equal than others in terms of the degree of state support that they can command. Missed interest and capital repayments are now becoming common among the weaker borrowers.

The performance of China’s producer price index provides additional support for our analysis. As the third chart shows, this is now flirting with a negative reading, suggesting that a decade of over-investment means that China now has a major problem of surplus capacity. This problem will, of course, be exacerbated if demand continues to slow in key areas. In turn, this suggests that the implications of our analysis go beyond Asian markets.

China still remains, after all, the manufacturing capital of the world, and its falling PPI implies that 2019 could see it exporting deflation. This would be exactly the opposite conclusion to that assumed by today’s rallying equity markets, although it would chime with the increasingly downbeat messages coming from global bond markets. Investors may therefore want to revisit their recent euphoria over the level of lending in China, and their new confidence that the so-called “Powell put” can really protect them from today’s global market risks.

Paul Hodges and Daniël de Blocq van Scheltinga publish The pH Report.