By John Richardson

YOU CAN make an argument that President Trump’s trade policies are good for SMEs that have lost out to China over the last 20 years. But even for some SMEs that source their raw materials from China, the trade war risks causing major damage.

Take the example of Colombia Sportswear of Portland, Oregon, that designs ski jackets and walking boots. It is very experienced in adjusting its sourcing strategy to minimise import tariffs, even ones that date all the way back to the 1930 Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act which made the Great Depression worse.

But this latest round of China-targeted US protectionism is proving a major challenge for the company because China is the only sourcing game in town, as it has come to dominate its raw materials supply. The same applies in many other industries.

The company can see the theoretical value of bringing manufacturing chains back to the US. But as Colombia Sportswear’s chief executive Tim Boyle points out:

This migration to Asia has been happening since the ’60s. And so everybody who made investments in machines to make fabric or extreme, you know, plastics to make nylon or any kind of textile products — all those investments have been in Asia. All the technology.”

It’s one thing to design a shirt like you’re wearing. You can sketch that out on a piece of paper. But to make it fit somebody, that’s a technical expertise in tailoring that doesn’t exist here anymore. You could come up with some stuff that nobody could wear.

To make the tariffs work, the US would have to launch major investments in new manufacturing facilities and in retraining workers in skills such as tailoring – a process that would take years.

And that is assuming that as the global economy slows down (my view is we are heading for a recession), and as US government debt repayments rise (one of the reasons why I believe we are heading for recession), the US can afford these investments.

Further, even in the best of economic circumstances, would the invisible hand of the market be sufficient to bring these investment about or would heavy government spending be necessary? If the latter is the case, how would heavy government spending fit with the Republican Party’s commitment to small government?

Big companies seem certain to lose out

In the case of big multinational companies, I find it harder to see how the White House’s trade policies will work in their favour.

Take GM as the most recent example of the damage being caused by the trade war. Its decision to cut jobs in the US and Canada was partly the result of tariffs on imported auto components.

And that of course gets me round to the subject of the US petrochemicals industry. Like GM, it simply must have access to the most important consumption market in the world by volume and by growth, which, as we all know, is China.

“None of the cracker-to-ethylene derivative plants that are now on-stream would probably have been sanctioned if boards of directors had known that there was a risk of losing access to the China market,” an industry contact told me on the sidelines of this week’s GPCA Forum in Dubai.

I can very much see his point as the US will need a 53% share of the remaining global LLDPE net import market if it cannot export to China in 2019, based on our estimate of its production next year. This compares to just 27% if it can ship to China.

In ethylene glycols, the US would also need 53% share of the remaining net import market if it cannot sell to China versus 9% if it can.

Both LLDPE and ethylene glycols are subject to 25% Chinese import tariffs, which, if they stay place next year, could make it unviable for the US to sell to China.

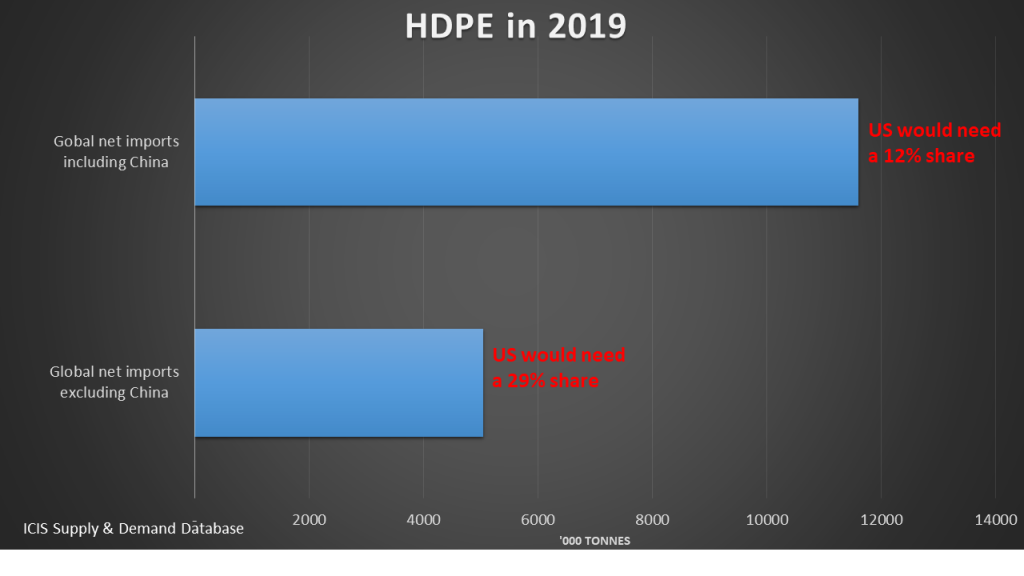

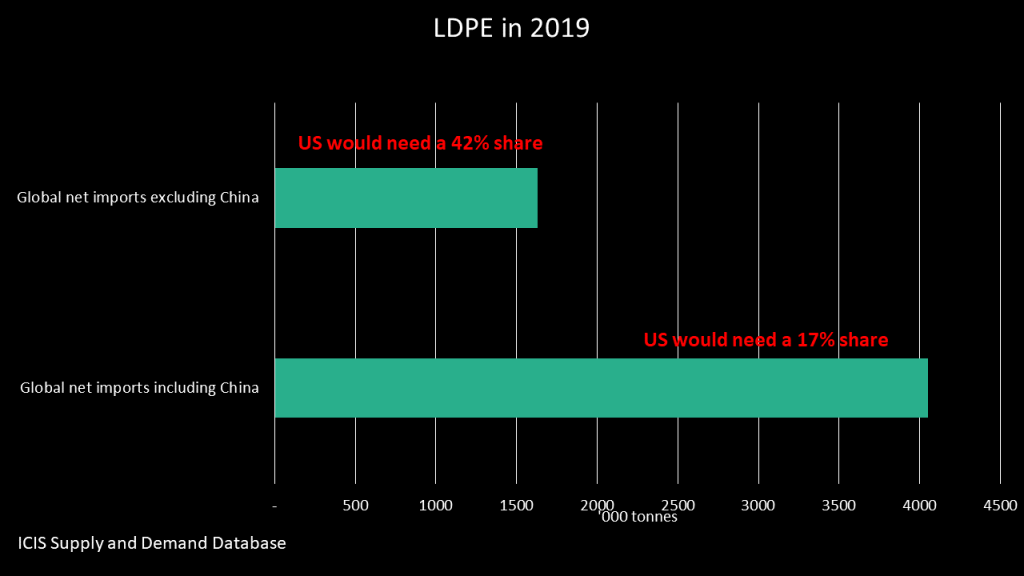

And my two charts in today’s blog post, covering HDPE and LDPE, show the same problems. HDPE is also the subject 25% tariffs, but LDPE faces no tariffs. This could change, though, if the trade war continues.

And note that even if the US petchems producers were prepared to absorb Chinese import tariffs, it seems doubtful that China would want to buy PE, ethylene glycols are any petrochemicals from China, assuming that the US/China relationship remains as bad as it is today.

Which is why US petchems and other manufacturers should hope that Presidents Trump and Xi can reach a deal this weekend at the G20 summit in Argentina. I hope I am wrong and any deal has real and lasting substance.