By John Richardson

IT IS BEING suggested that China’s “common prosperity” policy pivot, the biggest event in the global economy since at least 2009, will lead to a slowdown in local petrochemicals capacity additions.

Maybe. As we all know, our industry produces a lot of carbon emissions, and a key element of the policy pivot is cutting back on emissions as China tries to hit three targets.

The targets are limits on increases in carbon emissions set under the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025), reaching peak carbon emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060.

But what could instead happen is that whereas new coal-based projects will not be approved, new integrated refining-petrochemical sites would offer China a huge opportunity to take the global lead in carbon-mitigating technologies.

Building these new complexes would also fulfil China’s long-standing ambition for greater supply security – less dependence on imported petrochemicals and other raw materials.

Using existing and new refining-petrochemical sites to trial the technologies might be entirely in keeping with “common prosperity”, as it involves not just reducing carbon emissions, but also improving the quality of new manufacturing investments.

The quantity of manufacturing investments was the keystone post-2009, mainly for the economic multiplier effect of lots of construction activity. The focus on quantity over quality was one of the results of China’s giant economic stimulus package.

It was similar story in the real state sector after 2008. Many millions of new homes were built often for speculative purposes, leading to today’s vacant apartments that could house more than 90m people.

Five G7 countries – France, Germany, Italy, the UK and Canada – could each fit their entire populations into the empty Chinese apartments with room to spare,

Quality has become the focus of new investments – firstly, to reduce the carbon intensity of the economy, and secondly, to make sure a new factory or apartment building makes enough money to pay back debts.

There is a third element here too, and this is escaping China’s “middle-income trap” resulting from its rapidly ageing population.

Paying for “common prosperity”

Moving up the manufacturing value chain into state-of-the-art refining-petrochemical complexes that employ carbon limiting technologies would help justify the higher wages resulting from China’s greying population.

Here is another benefit: if China were to take the global lead in carbon-reduction technologies at petrochemicals plants, such as electric furnaces and blue and green hydrogen, it could make a lot of money as these look set to be high-growth global industries.

Higher profits would assist China in another key aspect of “common prosperity”, which is raising tax collection to pay for a better welfare system.

A better welfare system would help meet rising pensions and healthcare costs resulting from the ageing population, while also reducing income inequality – another objective of “common prosperity”.

It might be, though, that growth in petrochemicals capacity in general slows down because of the focus on quality over quantity – not just in the highly carbon intensive coal-to-petrochemicals sector.

Even with the best carbon-mitigating technologies, China might decide that too many new plants would have an unacceptable effect on its carbon balance.

And why build a lot of new refineries when electrification of transportation is picking up in China and elsewhere? You, of course, need refineries to supply feedstocks for petrochemicals plants, that is conventional feedstocks.

But what if China were to instead invest heavily in bio-refining and plastics recycling? Could these routes fill any feedstock-supply gaps resulting from a slowdown in building new conventional refineries?

Because of the difficulties in tracking what’s happening in China, a quite widely held perception is that cutbacks in on CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions are being pioneered by EU producers.

Consider, however, this ICIS Insight article from my colleagues Nigel Davis. He wrote:

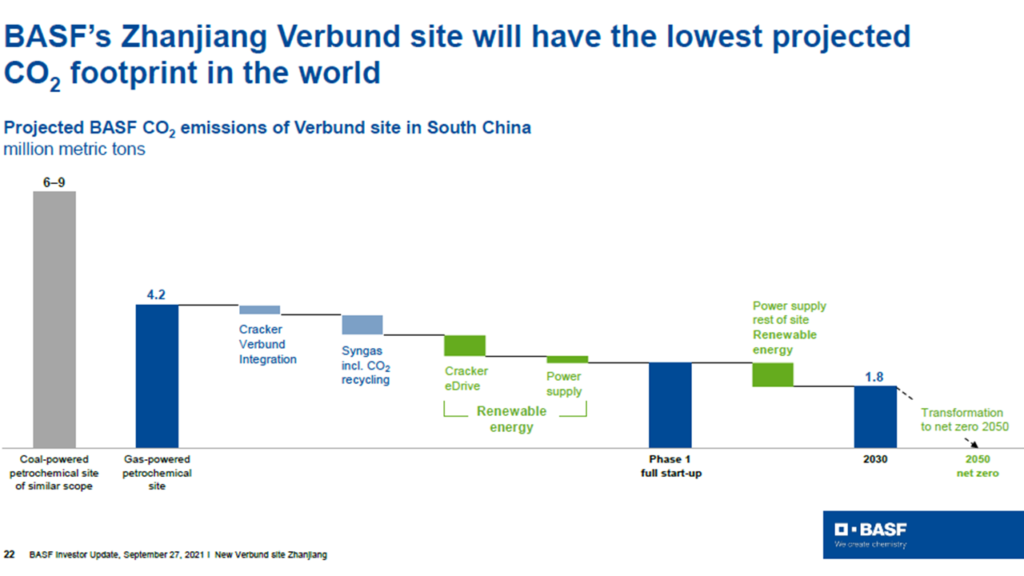

“BASF told investment analysts last week that Verbund planning for its new site in Zhanjiang, south China, which will be based around a flexible feed, butane, naphtha cracker, could deliver 60% lower CO2 emissions by 2030 compared with a gas-based petrochemical facility of similar scope.

“C3 chain production will use large amounts of synthesis gas utilising CO2 off-gas from ethylene oxide production and excess hydrogen from the 1m tonne/year cracker.

“Excess steam will be used to preheat air in the cracker furnaces. Fuel gas from an air preheating process will be used as a secondary feedstock for syngas.”

The fascinating BASF slide below claims that the new Verbund site in China will have the lowest CO2 footprint of any cracker complex in the world.

The right and wrong types of retrofitting

Retrofitting existing refining-petrochemical complexes with carbon-reduction technologies seems to make a lot of sense – as well as, perhaps, building new complexes.

But we must be careful of retrofitting old ideas, old ways of thinking about China, onto the entirely new development model that China is building.

Here is an example of the wrong type of retrofitting: the assumption that because people think China won’t build as many new petrochemical plants, its import dependency will not decline any further – and might even increase.

But there is every chance that demand growth will be a lot lower – at least in the medium and short-term – given that:

- 29% of the Chinese economy is dependent on real estate, the highest percentage in economic history.

- Real estate’s share of GDP increased by almost 10 percentage points (or about half the starting share) in the five years following the global financial crisis, and then stayed flat near 30. This means that these activities contributed nearly half of China’s strong GDP growth in those years, and a continuing near 30% or so of growth in the following years.

- “Houses are for living in and not for speculation” said China’s president, Xi Jinping, in a speech in 2017 as he laid the groundwork for today’s real-estate deleveraging. I believe that there will be no U-turn. The deleveraging will continue.

Weaker petrochemicals demand growth could thus mean no growth in imports or even lower imports, even if new capacity is cancelled.

Still unconvinced? Then look at the chart below where I show to scenarios for Chinese PP net imports in 2022-2025.

Under Scenario One, our base case, capacity between these years rises by 9.9m tonnes/year to 44.9m tonnes/year by 2025. Demand growth averages 4% per year.

Scenario Two involves the 3.9m tonnes/year of confirmed capacity to come onstream in 2022 o taking place as of course steel is already in the ground and it’s too late to cancel investments.

But let’s imagine that between 2023 and 2025 only 50% of the confirmed capacity happens. This means that rather than 9.9m tonnes/year of new capacity coming onstream in 2021-2025, only 8.3m tonnes/year happens

Then let’s cut average demand growth in 2022-2025 in half to 2%, perfectly reasonable given China’s reliance on real estate for its economic growth.

Just look at the difference! Our base case sees net imports at 4.1m tonnes in 2025; Scenario Two involves net imports of just 340,000 tonnes.

Note that in both scenarios I have kept average 2021-2025 operating rates conservatively low at an average of 80%.

Another outcome is that as China goes down the petrochemicals green path, it ensures its local producers are not placed at a disadvantage because of low-cost imports from overseas competitors who are not required to invest in carbon-reduction technologies.

I would not be at all surprised, therefore, to see China introduce a carbon border adjustment mechanism similar to the scheme being planned by the EU.

Nobody has a clue on how exactly China will get from A to B, from its old “get rich quick” approach to “common prosperity”. Anyone who tells you otherwise is being somewhat economical with the truth.

But what I see as set in stone is “common prosperity” as China doesn’t have any other choices.

It cannot continue to inflate the property bubble because of debt reasons, it must not allow income inequality to get any worse for the sake of social cohesion and it must raise its tax base to achieve greater equality and pay for an ageing population.

And as described above, further greening the economy dovetails with “common prosperity”.

This is a genuine paradigm shift and not a misuse of this often-overused phrase. Get used to it and plan accordingly.