By John Richardson

ONLINE SALES accounted for 19% of all retail sales in seven industrialised countries in 2020, up from 16% the year before, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

Year-on-year online sales growth numbers by country in 2020 included 59% in Australia, 46.7% in Britain and 14.6% in China, added UNCTAD.

In Australia, demand for semi-rigid takeaway restaurant food containers, made from homopolymer injection grade polypropylene (PP) rose by 70% in 2020 over the previous year, I was told by an Australian polymers industry source.

“Even though lockdowns ended in most parts of Australia from around April last year, people have got into the habit of buying more takeaway restaurant food. PP injection grade demand remains very good in 2021,” the source added.

US consumers spent $861bn online in 2020, 44% higher than the previous year, according to Digital Commerce 360 estimates. This was the highest annual US e-commerce growth in at least two decades. It was also nearly triple the 15.1% jump in 2019.

A survey of 2,000 American adults by McKinsey in November last year found that 40% of respondents intended to maintain elevated levels of online spending once the pandemic had been brought under control.

Some $14bn of funding has been poured into food-delivery start-up companies in the West, creating the potential that improved convenience will entrench changes in spending habits.

This could parallel what happened in China in 2015. During a very brief and mild economic downturn, people cut back on spending in high-end restaurants in favour of food delivered to homes from the restaurants.

In response, internet sales companies such as Alibaba boosted their food delivery networks.

Internet sales involve a lot more packaging

Because of the increased convenience factor, and because it has become fashionable, restaurant food delivered to homes has remained popular. Demand received a further boost during China’s pandemic lockdown.

“A lot of the smaller neighbourhood restaurants have shut down because of competition from online food delivery companies. Cheap as well as expensive food is being delivered,” said a polymers trader from Tianjin in China.

“And we are going the way of Japan as our population ages. Older people cannot get to the shops very easily, so more services are being developed for online food deliveries. The deliveries come wrapped in layers and layers of plastic,” he added.

A reflection of the boom in internet sales in general, not just in food, are Amazon’s sales figures.

The company reported net sales of $96.1bn in Q3 2020, a 37% increase from the same period in 2019. During the holiday season, the online giant delivered 1.5bn toys, home products, beauty and personal care products and electronics worldwide during what it called a “record-breaking” season.

Internet sales involve a lot more packaging than goods bought in brick-and-mortar shops, a 2018 Forbes article highlighted.

“Prior to the internet, the logistics for traditional retail were simple and linear – goods were shipped in bulk to a warehouse and then to the store. The system for e-commerce is much more complex,” wrote the magazine.

Quoting a white paper – Optimising Packaging for an E-Commerce World – Forbes said that e-commerce had about four times more touch points than regular retail, with shipments broken down into individual packages for delivery.

The average product bought online was dropped 17 times before delivery because of the large number of people involved in the logistics chain. This led to lot and protective packaging, said Forbes.

Returns of goods jumped 70% in 2020 compared with 2019, according to Narvar Inc, which processes returns for retailers. Sending goods back is particularly prevalent in clothing, where customers are obviously unable to try clothes on until they arrive.

When goods are returned, they don’t always come back in the same plastic and paper in which they were despatched. This means even more demand for polymers.

What will surely also continue to support polymers demand in packaging are increased hygiene needs. The precautionary principle is likely to mean continued elevated consumption of face masks, disinfectant wipes and hand sanitisers etc.

This is reflected in a very robust 2020 for LLDPE demand

Let me look at what happened to linear-low density polyethylene (LLDPE) demand in 2020 in the historical context before I consider some scenarios for future growth.

I will focus only on LLDPE in the rest of this blog post. I will consider the implications for internet sales and the demand for other polymers in future posts.

LLDPE is heavily used in packaging applications such as stretch and shrink film, bubble wrap and pouches.

In 2008, global LLDPE demand fell by 3% over the previous year because of the Global Financial Crisis.

US demand fell by an eye-wateringly high 16% in 2008 before recovering to 6% growth in 2009. But in Europe, as the financial crisis morphed into a sovereign debt crisis, consumption contracted by 3% in 2008 and then by 10% in 2009.

But because of the internet sales boom, increased hygiene needs – and perhaps a more temporary boost from greater surface area of demand as people bought more food from supermarkets and less from restaurants – demand growth in 2020 was robust.

Local US LLDPE demand in 2020 grew by 2.6% over the previous year as exports also surged, said CDI, the ICIS US-based petrochemicals and polymers data and analytics service.

I believe it is reasonable to assume that other developed markets grew by around the same amount. Let us for argument’s sake assume that European demand also increased by 2.6%, with consumption in Canada, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan increasing by the same amount.

Chinese demand rose by 14% in 2020 over 2019, according to my estimates.

If you then assume positive growth in South & Central America and Turkey, but minus or flat growth in Africa, the Middle East, Asia & Pacific and the Former Soviet Union, the net result is 5% global growth in 2020 over 2019.

This would leave global demand in 2020 at around 40m tonnes. Growth of 5% last year would be the same as growth in 2019 over 2018 – in other words, no overall coronavirus downside.

Please note that as always, the above numbers are not our official estimates for 2020 and only represent my guesstimates of what happened. The same applies to the forecasts that follow.

All my numbers are always meant for demonstration papers only to indicate what I believe are the overall trends. For proper demand crunching and scenario work, contact me at john.richardson@icis.com and I can put you in touch with our analytics and consulting teams.

Three scenarios for global LLDPE demand in 2021-2025

I could be wrong about a continued boom in internet sales and elevated hygiene needs providing further support for global polymers demand. It has been known. I have been wrong in the past.

More broadly, we also live in a world of exceptional uncertainty and volatility. The number of variables out there are nothing short of bewildering. This is certainly the most difficult time for forecasting in the 24 years I’ve been analysing the petrochemicals business. If you disagree, I suggest you think again.

You must therefore adopt a scenario-based approach – hence, my three scenarios for LLDPE demand you can see in the slide at the beginning of this blog post:

- Scenario 1 assumes global demand growth will average 6% in 2021-2025. Consumption rises from around 43m tonnes in 2021 to 53m tonnes in 2025. Global operating rates average 91%. This would compare very favourably with operating rates in 2000-2019 that we assess at 84%.

- Scenario 2 assumes consumption expands at an average 4% per year. Demand grows from 42m tonnes in 2021 to 50m tonnes in 2025. Operating rates average 86%.

- Scenario 3 involves average growth of 2% including negative growth in 2021 over last year. Demand rises from around 40m tonnes in 2021 (some 360,000 tonnes smaller than my assumption for 2020 when you look at the exact numbers) to 45m tonnes in 2025. Average operating rates are a painfully sub-par 80%.

Want my opinion? Scenario 3 is extremely unlikely because of the trends I’ve highlighted above. Scenarios 1-2 seem probable.

“But hold on,” I can hear you say, “you’ve been going on and on about increasing Chinese petrochemicals self-sufficiency and our industry moving from a world of price inflation to deflation.

You are of course right. But while this applies to PP, styrene monomer, paraxylene and ethylene glycols – and perhaps also to high-density PE and low-density PE if China partners with Iran – it does not apply to LLDPE, based on our data. Let me explain why.

In the worst-case outcome, Chinese imports at 11.3m tonnes in 2031

We do not have enough unconfirmed projects in China that could push the country anywhere close to LLDPE self-sufficiency. This the opposite of PP where there are enough unconfirmed projects to shift China to an export position in 2026 from last year’s imports of 6.6m tonnes.

Unconfirmed projects are projects we have listed with question marks in our data base where financing, feedstocks, technologies or approvals have yet to be secured.

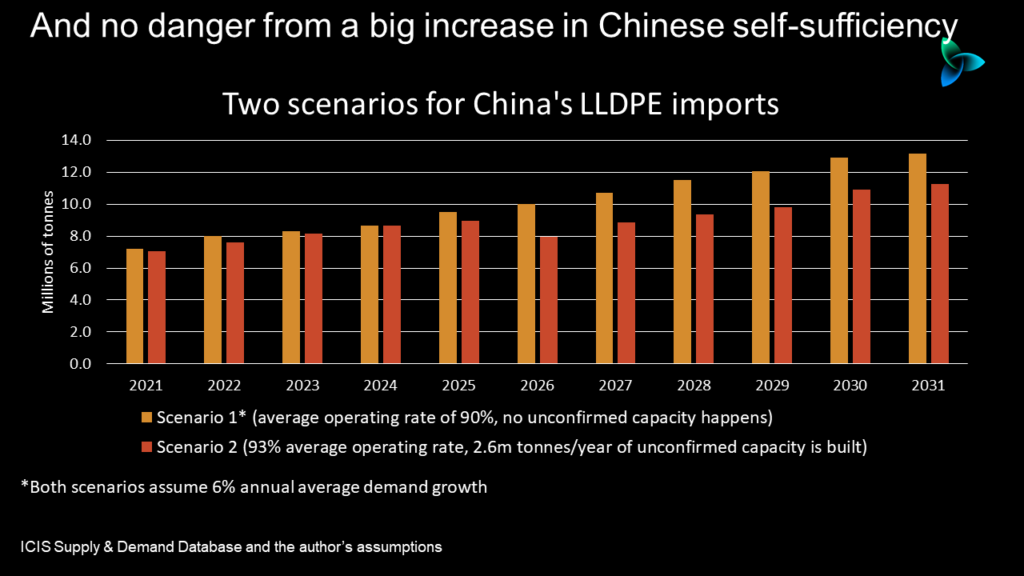

I have extended my forecast period beyond 2025, right out until 2031, to provide you with a longer-term view of Chinese LLDPE imports (see the slide immediately above).

Scenario 1 in the chart, our base case, assumes an average 2021-2031 operating rate of 90% and none of the 2.6m tonnes/year of unconfirmed capacity goes ahead. Scenario 2 involves a 93% operating and all the 2.6m tonnes/year of unconfirmed capacity going ahead.

Both scenarios are built on the same demand growth estimate – our base case – of an average 6% growth in 2021-2031.

Even under Scenario 2, imports are still 11.3m tonnes in 2031 versus 13.2m tonnes under Scenario 1.

As with many other petrochemicals and polymers, China completely dominates the global LLDPE import markets. We estimate that in 2020, China accounted for no less than 61% of total global net imports among the countries and regions that imported more than exported. Europe was in distant second place at 15%.

This explains why China’s inability to significantly raise its LLDPE self-sufficiency is so significant.

An even greater sustainability challenge

Robust LLDPE demand growth would add to what are already big sustainability challenges. Think of the extra consumption of stretch and shrink film, bubble wrap and pouches.

The developing world is home to some 3bn who lack either access to any rubbish collection systems at all or adequate systems.

Until or unless good-enough collection and landfill systems are built for these 3bn people, the plastic waste crisis will not be resolved.

This is a topic we simply must bear in mind every time we consider scenarios for demand growth for any polymer.

At least in the developed world, extra LLDPE demand should not create more of a plastic waste crisis because most waste is already collected – and it can no longer as easily be exported to the developed world.

But because of weak collection systems – and because of the vast majority of LLDPE demand growth will be in the developing word – the focus, as I said, has to be on improving collection systems.

But from the short-term dollars and cents perspective, LLDPE will in my view be a winner over the next few years. Downcycle? What downcycle? I don’t see the long-predicted supply-driven downcycle in LLDPE happening.