By John Richardson

DIFFICULT choices lie ahead for exporters of polypropylene (PP), styrene monomer (SM) and paraxylene (PX) to China. From next year onwards, the country’s imports will start to decline and by 2023-2025 complete self-sufficiency may be reached in all these products.

Just how significant this shift will be for global markets, we can see from the ICIS Supply & Demand Database estimates of China’s 2020 share of total global net imports. This is amongst the countries and regions in the world that will import more than it exports. In PP, China’s share of global net imports is estimated at 43%, at 69% for SM and a huge, eye-wateringly disproportionate 90% for PX.

Alternative approaches for PP and SM exporters

Perhaps in PP, alternative destinations can be found that can repair most of the holes in China-centric business models. This could be combined with moving into higher-value grades of copolymers that China will perhaps (or perhaps not…see my later comments) still need to import.

And maybe, too, SM that can no longer be shipped to China can be turned into derivatives. But producers will have to pick and choose their derivatives and grades of derivatives. China dominates global production of general-purpose polystyrene (PS) and high-impact PS for instance.

But might there be some space in alloys of acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene (ABS) with polycarbonate? This is one of the innovation spaces in which ABS can be lifted from being a commodity to an engineering polymer.

Can companies in the styrenics polymer space in general innovate to take advantage of further light-weighting of vehicles as electric vehicles rapidly replace internal combustion engines? Because of the heavy weight of electric batteries, further light-weighting could be important in increasing the distances between recharges.

And to a limited extent, membership of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) will provide support. The long-negotiated trade deal includes harmonisation of rules of origin.

If PP and SM are exported from member countries to China – which is also of part of the RCEP – tariffs will be reduced if the imports are to be re-exported as finished goods. This is provided that exports go to any of the 15 RCEP members.

China’s top 10 PP trading partners based on 2020 import data and in descending order of market shares that are part of the RCEP are as follows: South Korea, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam and Japan. Out in the cold as non-members of the RCEP are Taiwan, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia and India – again in descending order of market shares.

It easy to imagine what might happen. In January-September 2020, Saudi Arabia had a 10% of share of the total market and the UAE and India each had 8%. South Korea, the market leader with a 20% market share in 2020, might win much more market share from the three outsiders.

In SM, Saudi Arabia appears to be particularly vulnerable as it is China’s No 1 source of imports. In 2020, Saudi Arabia has taken a 33% share of total China imports. It may in future face stiffer competition from Japan, Singapore, South Korea and Malaysia, which are also amongst China’s top trading partners and are members of the RCEP.

But membership of the RCEP will not make a great deal of difference over the long term, in my opinion. I can see no scenario under which China will stop pushing hard towards PP and SM self-sufficiency.

China will continue to build PP plants as this is a polymer that China can use to help escape its middle-income trap. The focus will thus not just be on homopolymer production but also on copolymers.

It is widely and I believe wrongly assumed that China will remain a big importer of copolymers because it lacks the technologies. But this conventional thinking ignores history. The history of manufacturing in general in China is full of examples where China has surprised the sceptics with its technological progress.

And you must think about China’s pressing need to escape its middle-income trap, to justify wages that will continue to rise as its working-age population keeps on shrinking. China might one day be able to reverse the ageing of its population. But this is a long shot, at best.

Government subsidies will therefore be maintained at high levels for research into locally owned higher-value technologies. Why shouldn’t PP be amongst the technologies that attract this kind of support?

There is an opportunity for overseas producers who also own the licenses for copolymer PP technologies. China will, I believe, continue to search for joint-venture partners for new local capacity.

Because SM is a highly commoditised petrochemical, the logic of self-sufficiency is almost entirely about local supply security in a very uncertain geopolitical world (this is a secondary factor behind the push towards PP self-sufficiency).

Achieving SM self-sufficiency would also be a by-product of the decision taken in 2014 to achieve complete self-sufficiency in PX. The mixed xylenes and toluene being produced to convert into PX will yield large quantities of benzene. Benzene and ethylene are the main feedstocks for SM.

The difficult choices made by PP and SM exporters to China may sadly not just relate to downstream diversification; plant closures may also be necessary.

In PX there appears to be no “maybe” about plant closures

Plant closures in PX seem inevitable because China will account for 90% of global PX net imports in 2020. If China becomes self-sufficient, and I think this will happen, remaining global imports would be too small to accommodate today’s capacities.

China also completely dominates the global downstream polyester fibres, polyethylene terephthalate (PET) film and PET bottle markets. This leaves no opportunities for PX exporters to add derivatives capacity as a means of absorbing their surpluses.

Members of the RCEP might again be able to win market share over the short term versus non-members. But this would only delay some very difficult calls by a few years.

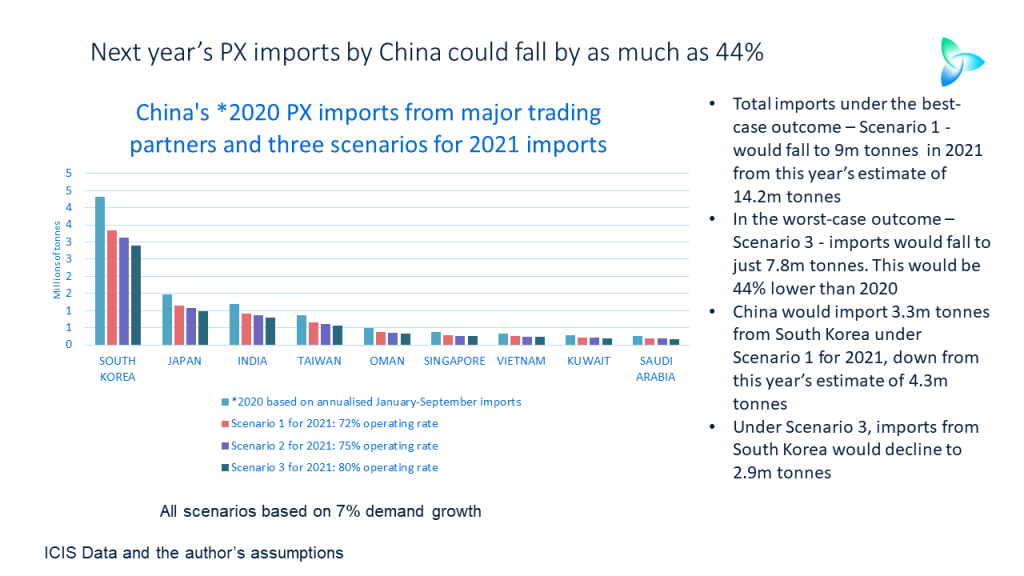

Now let us look at scenarios for China’s PX imports. Let’s begin with the chart at the beginning of this blog post.

This shows three scenarios just for 2021 broken down into imports by China from its major PX trading partners. The three scenarios assume different operating rates at plants that are already on-stream or that we believe will start up next year (unlike my second chart at the beginning of this section, no unconfirmed capacity is included here).

In terms of total imports, under the best-case outcome for 2021 – Scenario 1 – imports would reach 9m tonnes compared with a 2020 estimate of 14.2m tonnes. In the worst-case outcome – Scenario 3 – imports would decline to just 7.8m tonnes.

South Korea is China’s biggest trading partner followed by Japan. In 2020, South Korea has won 37%of the total China import market followed by Japan at 12%

China would import 3.3m tonnes from South Korea under Scenario 1 for 2021, down from this year’s estimate of 4.3m tonnes. Under Scenario 3, imports from South Korea would decline to 2.9m tonnes. China would import 1.1m tonnes from Japan in 2021 under Scenario 1 compared with an estimated 1.5m tonnes this year. Scenario 3 would see imports slipping to 1m tonnes.

All three scenarios assume very robust demand growth of 7%. This would compare with the 14% rise in apparent demand that we saw in January-September, with the decline the result of moderation in Chinese clothing and non-apparel export growth.

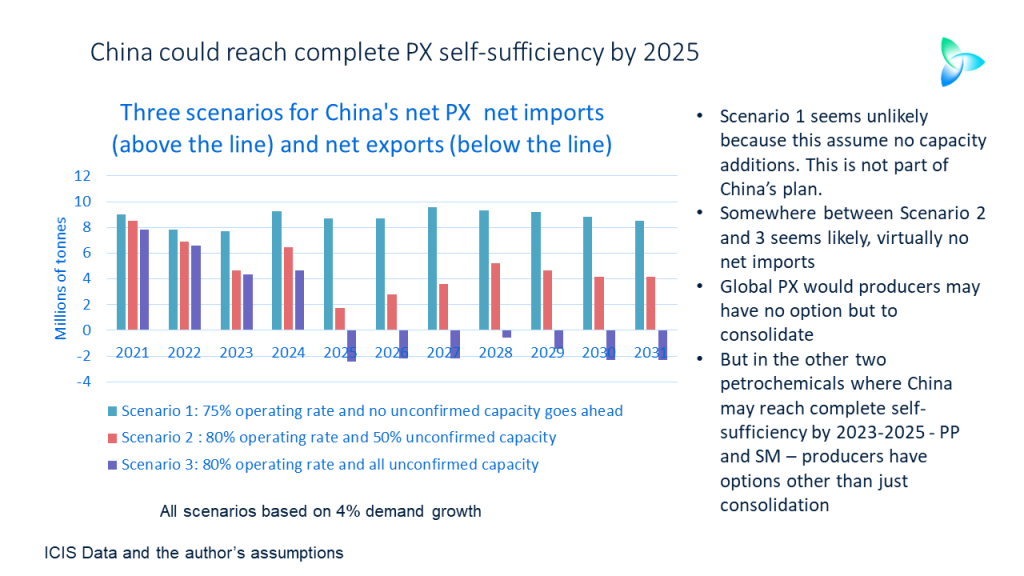

Now let us study my second chart at the beginning of this section on PX.

All the scenarios assume average demand growth of 4% in 2021-2031 with three different outlooks for operating rates and the amount of unannounced capacity that goes ahead.

I cannot see no unconfirmed capacity taking place because this does not fit with China’s strategic ambitions to raise, not only its PX capacity but also to build a stronger position in upstream refining.

As with PP and SM, this is about supply security in a very uncertain geopolitical world. PX self-sufficiency is also to do with fixing the problem created by the big wave of standalone purified terephthalic acid investments that took place from 2009 onwards.

In Scenario 1, China would still import 8.7m tonnes in 2025. But under Scenario 2, imports would decline to just 1.7m tonnes and in Scenario 3, China would switch into a net export position of 2.4m tonnes.

Realistically, because export markets ex-China are so tiny, I see local producers gauging operating rates to achieve just about complete self-sufficiency. So, expect somewhere between Scenarios 2 and 3.

At first glance, all seems right with the world under Scenario 1 in 2031, as net imports would be at 8.7m tonnes. But that would still be 67% lower than 14.2m tonnes – the estimate for 2020.

Under Scenario 2, net imports would be at 4.1m tonnes in 2031. Scenario 3 would see net exports at 2.3m tonnes. I again expect somewhere between these two outcomes as China reaches close to a balanced position.

Conclusion: separating the Winners from the Losers

It does seem as if China will remain a substantial polyethylene (PE) and ethylene glycols (EG) importer over the next ten years. But, as my forecasts for imports in 2021 show for both these products, substantial declines in imports are possible.

China’ shift to self-sufficiency fits in with two of today’s four megatrends: demographics and geopolitics. Its ageing population is obviously a demographic trend. An ageing population means higher labour costs. Hence the push into higher-value manufacturing, including copolymer PP, that compensates for the economic disadvantages of higher wages.

China’s big split with the US, which began around four years ago, ended a benign period in world history that started with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. During this period there was no Superpower competition.

China is making great progress in building alliances with the rest of the developing world as part of its struggle with the US. This gives it the opportunity to buy whatever petrochemicals it will need at competitive prices from fellow developing world countries, thanks to both the RCEP and China’s broader Belt & Road Initiative.

But China cannot possibly know, as the rest of us cannot possibly know, how the Superpower struggle will ultimately play out and who will end up as its trading and geopolitical partners versus its adversaries. So, why would China take the risk of remaining heavily dependent on petrochemicals exports given the risk of geopolitics-related supply disruptions?

China has state-of-the-art new petrochemicals sites that will continue to attract plenty of domestic and overseas investors, along with, of course, the fastest growing market in the world with huge potential for further demand growth.

I have made some suggestions in this post about what petrochemicals exporters might be able to do in response. These are just tactical responses. But what will strategically sort the future Winners from the Losers is how they respond to the four megatrends. In no order of importance, they are: demographics, geopolitics, sustainability and the pandemic.

The ability to recognise and work effectively with these trends will separate tomorrow’s Winners from the Losers.